GOLDSEA | ASIAN BOOKVIEW | MEMOIRS

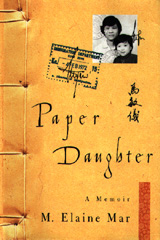

Paper Daughterby M. Elaine Mar

HarperCollins, New York, 1999, 292 pp, $23

The hilariously candid and moving record of a Chinese American's progress from young Hong Kong immigrant to Harvard student. Highly recommended.

EXCERPT

y memory begins with the taste of chicken blood. Coaxed from the two-bone middle section of the wing, the crack of bone splintering between my teeth, the clotted marrow heavy on my tongue -- the memory of sweetness began before language, desire born before knowledge of the words to describe it.

y memory begins with the taste of chicken blood. Coaxed from the two-bone middle section of the wing, the crack of bone splintering between my teeth, the clotted marrow heavy on my tongue -- the memory of sweetness began before language, desire born before knowledge of the words to describe it.

Until I was five, I lived in a tenement house near the Hong Kong airport, on the Kowloon side of Victoria Harbour. Our building was a narrow eight-story walkup, a tired-looking column streaked dark with humidity and soot, faceless, unadorned, indistinguishable from any other building in the project. Inside, the walls were concrete, the stairways dimly lit, the landings littered with residents pausing to rest on their climb to the upper floors. Passing neighbors' hellos, their whines, complaints, and words of encouragement, were obscured by the roar of airplane engines vibrating through porous cinderblock.

My parents and I lived on the fourth floor -- a stroke of luck, according to my mother, who recognized good fortune in my guise. She didn't mind that we shared a five-room flat with four other families; that our central hall stunk of salted fish and day-old rice; that water only ran three times a week. For her, it was enough that we could make it home without once resting on the stairs. Home, with breath to spare -- what more could we ask?

My father was different. He didn't talk about luck, preferring instead to rely on his own wits. He'd discovered our flat the old Cantonese way -- through long afternoon grumbling in tea shops with his cronies, slipping housing inquiries in between puffs on his cigarette, in between the obligatory complaints about the government and Hong Kong's outrageous cost of living. He'd waited through the useless replies: the long-winded formulas for improving the economy; the canny, ever-changing predictions about Hong Kong's future; the wistful, oft-repeated plans to leave Kowloon's projects for untold riches in America. He'd listened to old men describe their latest ailments. He'd commiserated with the young ones who cursed their bosses. He'd nodded and sighed, swirling the tea at the bottom of his cup. And finally, after weeks of tea and cigarettes, he'd heard about the flat on Ying Yang street, near the Hong Kong airport.

Four rooms each measuring ten feet by ten, a smaller fifth room, every room opening onto a central hallway. A toilet at the end of the hall, shielded by a sackcloth sheet. Enough floor space to cook in the entryway. Overall, the apartment totaled less than six hundred square feet -- but the number was irrelevant: Who could afford an entire flat? One family, one room -- that was the way we lived in Hong Kong. My parents, newly married, chose one of the larger rooms, away from the stench of the hall toilet. They furnished it with a sturdy metal bunk bed, a chest of drawers, folding chairs, and a collapsible table. They filled the bureau's drawers with thin cotton undershirts, flannel pajamas, my mother's nylon stockings, my father's brown knit socks. On the bed's top bunk they stacked ricebowls and chopsticks, cases of noodles, sacks of rice, glass jars heavy with dried herbs and bark. Then, amid the foodstuffs' delicious wild scent, my parents lay, squeezed together on the bed's lower berth, blessing the room with their desire for a family.

ASIAN AIR ISSUES FORUM |

CONTACT US

© 1999-2003 GoldSea

No part of the contents of this site may be reproduced without prior written permission.