|

ASIAN AMERICAN PERSONALITIES

Susan Choi makes a luminous stand at the subversive, secret intersection between mistrust of society and the struggle for emotional survival.

|

CONTACT US

|

ADVERTISING INFO

© 1996-2013 Asian Media Group Inc

No part of the contents of this site may be reproduced without prior written permission.

GOLDSEA | ASIAMS.NET | ASIAN AMERICAN PERSONALITIES

Shadow

Novelist

PAGE 1 OF 4

he past decade produced two Asian Americans universally hailed by the literary establishment as possessing first-order novelistic talent. Both are Corean American. Susan Choi is easily the lesser-known of the two, but not necessarily the one possessing lesser talent. If anything, her first novel (The Foreign Student, HarperCollins, 1998) brims with more promise than Chang-rae Lee's Native Speaker in terms of narrative intensity, emotional maturity and fragrance, that hallmark of Southern novels.

he past decade produced two Asian Americans universally hailed by the literary establishment as possessing first-order novelistic talent. Both are Corean American. Susan Choi is easily the lesser-known of the two, but not necessarily the one possessing lesser talent. If anything, her first novel (The Foreign Student, HarperCollins, 1998) brims with more promise than Chang-rae Lee's Native Speaker in terms of narrative intensity, emotional maturity and fragrance, that hallmark of Southern novels.

It also holds ample evidence of the quality that augurs continued critical acclaim but media obscurity: an aversion to direct sunlight. The novel is dusty, not to say yeasty. It progresses more by fermentation of accumulated detail rather than by anything resembling action or, heaven forbid, plot. The words seem to have been layered on the page in tightly overlapping swirls in a process reminiscent of ion deposition.

It is an inevitable reflection of the author's passion for shadow. Drawn by her striking talent, an interviewer succumbs to a natural curiosity about the divorce between her Corean father and her Russian Jew mother when Choi was nine. She responds with a cold, "That's nobody's business but theirs." Ask her to describe her days as a factchecker at the New Yorker and she becomes downright derisive. The word speaks for itself and she isn't about to demean herself by supplying personal color. Her apparent disdain for on-record chitchat contrasts with the cordially conscientious tone of our preliminary communications.

In print at least Choi prefers the light from a dusty gooseneck lamp and likes it spotted tightly, thank you, and preferably from an obscure angle. Fortunately, this passion for obscurity, this astringent impulse, finds favor with academics, literary critics and others who see themselves as footsoldiers of refinement in a media world run amuck with color. But even they must have become antsy waiting five years for this prodigy to deposit her second novel.

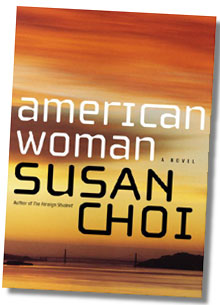

But it is finally August 2003 and Choi's number two is being published. It is titled American Woman, an obvious play on the title of her first. The juxtaposition might suggest a novel with more color and creature comforts than the eerily muted 1950s pas de deux between a penniless Corean immigrant and a damaged southern heiress. But no. The American woman is a Japanese American radical on the lam in a traumatized 1970s America. Like the characters in TFS, Jenny inhabits that subversive, secretive intersection between mistrust of society and the struggle for emotional and physical survival. She is modeled closely after Wendy Yoshimura, a figure inextricably linked to the terrorist group that kidnapped heiress Patty Hearst.

Choi admits to struggling with the starts of her novels and the reader feels her pain while trying to gain traction with AW. But he is rewarded. Like TFS, the narrative is memorably intense, mature and, not fragrant exactly, but mustily and convincingly atmospheric. Like the first, it ferments into memorable wine, the expensive kind with the hand-lettered labels.

Susan Choi was born 34 years ago in South Bend, Indiana. Like the protagonist of TFS, her father had come from Corea to attend the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee. He met Susan's mother, daughter of a Russian Jewish immigrant couple, at the University of Michigan. They divorced when Susan was nine. She moved to Houston with her mother. She graduated from Yale with a BA in literature in 1990. She spent two years in a succession of odd jobs before enrolling at Cornell. She left nearly three years later with a masters in fine arts and a 5-page fragment based on her father's oral accounts of his first years in the United States. About a year after moving to New York to work as a factchecker at The New Yorker, she began the laborious process of expanding the fragment into The Foreign Student. It was published in 1998 to critical raves.

CONTINUED BELOW

GS: Tell us about your childhood in Indiana through age 9. (e.g. Were you an outcast or the popular kid? Were you a bookworm or a bully? Did you fight with boys or like them?)

SC: I think I was a pretty average suburban kid. When my girlfriends and I played Charlie's Angels I always got to be Jill. I did attend a school at which I can recall in my grade exactly one Black student and one other Asian, a kid named Cesar Aquino who was periodically selected as my future husband for the 'so and so and so and so, sitting in a tree,' rhyme. It was pretty good natured but obviously, Cesar and I were destined to wed in the eyes of our classmates because we were both Asian. I actually ran into him decades later in Ann Arbor Michigan. I think he'd become a successful businessman.

GS: We know that your father is Corean. Tell us about your mother and how she met your father.

SC: My mother is the youngest of the nine children of a pair of Russian Jewish immigrants who settled in Detroit. My mother met my father at the University of Michigan.

GS: Your parents divorced when you were nine. Why did they divorce?

SC: I don't really think thatŐs an appropriate question. That's nobody's business but theirs.

PAGE 2

| "Choi prefers the light from a dusty goodseneck lamp and likes it spotted tightly, thank you, and preferably from an obscure angle." |