|

GOLDSEA |

ASIAMS.NET |

ASIAN AMERICAN PERSONALITIES

THE 130 MOST INSPIRING ASIAN AMERICANS

OF ALL TIME

Hiro Narita

PAGE 2 OF 3

t the end of 1965 he returned to apprentice with Korty. Narita found himself designing posters, helping with promotional duties, and assisting Korty's cameraman on educational films. There were moments of self-doubt when Narita no longer felt sure he could succeed as a cinematographer. So he continued working as a graphic artist while aspiring to work behind the camera.

t the end of 1965 he returned to apprentice with Korty. Narita found himself designing posters, helping with promotional duties, and assisting Korty's cameraman on educational films. There were moments of self-doubt when Narita no longer felt sure he could succeed as a cinematographer. So he continued working as a graphic artist while aspiring to work behind the camera.

Others may feel that from a graphic artist to a cameraman was a change of field," he says. "Not for me. They both deal with storytelling, essentially."

In 1970 Narita began freelancing as an assistant cameraman. "It was not easy to make a living," he recalls. He worked on a succession of low-budget films whose titles he scarcely recalls. One was Silence, about a deaf child lost in the forest. "Those movies were just soap operas," he says. But they were good experience. It took him almost ten years to establish himself.

Meanwhile, Korty hadn't forgotten him. He asked Narita to shoot a television film about the Japanese American internment camp experience called Farewell to Manzanar. It won Korty acclaim and Narita his first Emmy nomination. He considers Manzanar to be the true beginning of his career as a cinematographer. It was followed by several more TV films and segments of Vegetable Soup, a children's program for PBS which aired during the late 1970s.

The work of documentaries and television films didn't help Narita acquire real stature as a cinematographer. For that he needed to work on theatrical features. His only such experience had been as one of several cinematographers on Martin Scorsese's The Last Waltz.

His first chance to catch Hollywood's eye was on Ballard's Never Cry Wolf, a Walt Disney film released in 1983 on which future wife Barbara was script supervisor. Based on an autobiographical account of biologist Farley Mowat, Never Cry Wold contrasts man's threat to the environment with the econologically benign role played by the much-maligned wolf. The film is full of powerful and arresting visuals that derive from the beauty of nature. At the same time Narita and Ballard worked to give the film a gritty, and at times, a downbeat look. Wolf won raves for its theme, direction and photography and even became a modest box-office hit. Competing against big-budget films like Return of the Jedi and Ghostbusters, Narita won an award from the National Society of Film Critics. The critics found Wolf's stark visuals a refreshing change from the postcard quality of many Disney films.

Some critics proclaimed the photography of the wolves and other natural phenomenon to be superior to anything since Disney's True Life Adventures made in the 1950s and early 60s. Variety praised Wolf for its departure from the usual outdoor elegy, and credited the two years of painstaking effort that went into filming with having helped achieve its "powerful images and comprehending feel for the wonders and mysteries of mother nature."

"Director Carroll Ballard took a big chance with me," Narita says. He notes that because of the earlier success of Ballard's The Black Stallion, he could have hired any Oscar-winning cinematographer to shoot Wolf. Narita thinks one reason Ballard chose a relative unknown was the desire to work with someone who would respond with an open mind to the script's challenges.

Most Hollywood films are shot in nine months or less. Wolf was shot over a two-year period in Oregon and the Canadian Arctic. Among the most difficult scenes to capture was one showing a pack of semi-domesticated wolves running in one direction and the actors running in the other.

"To synchronize the five minute sequence, I shot thousands of feet for almost five weeks," Narita says. "It was summer in Alaska, and we had to shoot between two and five in the mornings as the days were unbearably hot."

While working on Wolf Narita formulated a criterion for taking on a project: the story. He took on special-effects-laden films like Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, The Rocketeer and Star Trek VI only because of their strong story concepts.

"I go for scripts with a strong story that deals with human relationships," Narita says. "If a script is packed with special effects and little else, I would rather not work on it." Two movies he would like to have done are My Left Foot and Driving Miss Daisy. He admires their emotional intensity.

Honey, another Walt Disney production, was the directorial debut of John Johnston whom Narita had met at Industrial Lighting and Magic, the special effects factory owned by filmmaker George Lucas. Narita was doing effects photography for ILM and Johnson was creating special effects for films like Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Released in 1989, Honey grossed $300 million worldwide to become one of the ten most profitable films of all time. It is a cute comedy about a quartet of kids who accidentally trigger an experimental ray gun that reduces them to microscopic size. Tossed out of the house with the contents of a dustbin, the kids overcome awesome obstacles to return to normal size.

By shooting most of the film at the sprawling Chubasco Studios in Mexico City, the producers saved $6 million and brought it in for $18 million. The leisurely pace at which the Mexican crew worked prolonged the team's separation from their families. Narita spent more than nine months photographing the action among gargantuan sets representing, among other things, an entire suburban neighborhood, complete with barbecues and redwood benches.

Disney's top sci-fi brains and technicians were flown in to Chubasco Studios. Narita learned that mechanical wizardry could neither solve all problems nor create the desired effects.

"One set had oversized grass made out of plastic and foam," he recalls. "Somehow it didn't seem right. I wondered how to make it real. The solution, when it came, was simple — we sprayed the grass with water so often that it looked real."

PAGE 3

Page 1 |

2 |

3

Back To Main Page

|

|

|

|

|

“To synchronize the five minute sequence I shot thousands of feet for almost five weeks.”

|

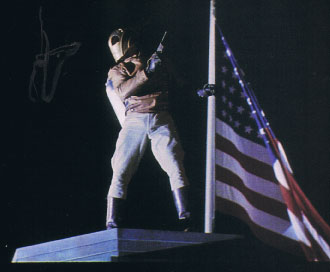

The Rocketeer (1991) was a beautiful big-budget Narita project that failed at the box office.

|

CONTACT US

|

ADVERTISING INFO

© 1996-2013 Asian Media Group Inc

No part of the contents of this site may be reproduced without prior written permission.

|