It isn’t easy for an Asian writer — or any writer for that matter — to achieve the level of success enjoyed by the likes of Amy Tan and David Henry Hwang. But the degree of acclaim their works have enjoyed has always made me ambivalent.

What turned my ambivalence into outright disgust is Joy Luck Club, the movie. It does nothing to enhance or balance the prevailing image of Asians in the American media. Instead it caters to the most chauvinistic impulses fueling Hollywood portrayal of Asians. Not to beat around the bush, the movie caters to two groups: Caucasian men and Asian women who are discomfited by Asian men. And it does so entirely at the expense of Asian men, and ultimately, of all Asian Americans.

The movie is premised on the suffering of four Chinese mothers whose lives are so un-credibly pathetic (bathetic?) that they verge on the comical. How many Asian American women have been forced to abandon two daughters by the side of a road, drown an infant son to avenge the cruelty of her playboy husband, or forced into concubinage by her own malign family? Not one of these unfortunate women’s stories contains a single sympathetic Asian male character. Their tales of woe depict Asian males as crass, cruel, weak or simply non-existent. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? It’s typical of the worst products of white Hollywood exploiting Asians as a handy foil to demonstrate the superiority of white America.

Here’s the payoff. Each of these unfortunate women bears a daughter who, to a greater or lesser degree, is given the option of suffering her mother’s sorry fate by proxy or escaping this whole gruesome Asian scene by marrying a white man. Well, what is a rational girl to do?

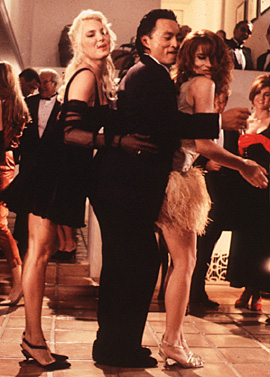

Of the four daughters, the two who are more spirited and physically attractive marry Whites. Both white husbands are successful and attractive notwithstanding one or two cute, understandable flaws corrected in the course of the movie. One is a lawyer, the other is the dashing scion of a publishing family.

The third of the daughters — the simpering loser of the bunch — is given an Asian husband who is financially successful but pathetically miserly, geeky and cold. He insists on maintaining separate checking accounts and keeping a list on the refrigerator of every item of grocery either of them buys so that at the end of each month they can split the total. I found this character not only offensive but downright un-credible.

As a group we Asian men may possess our share of unappealing characteristics, but miserliness with groceries isn’t one of them. Every Asian male I know turns over care of the checkbook to the wife. I know of a number of Asians who are tight-fisted but none stingy enough to make the wife pay for half his ice cream habit. In fact, most Asians I know are baffled by the sight of groups of white people divvying up the restaurant tab.

As for the fourth daughter, the narrator, the only man in her life is a doddering father.

Where are the Asian men in this universe?

I understand that this pastiche of stories is supposed to be about mother-daughter relations, but how validly and interestingly can that be explored in a world devoid of credible Asian males? Not even the most radical feminist, I suspect, would argue for that particular vision of the universe.

The net effect of the Joy Luck Club — which could more aptly have been titled Joyless, Luckless Club — is to reinforce existing strereotypes in which Asian life is miserable and cheap and Asian women are plentiful and available in the absence of virile, sympathetic Asian males. What’s more, it subtly supports the notion that the faults of white males are superficial, even cute, and easily correctible (i.e., learning to use chopsticks, learning not to slop soy sauce on the mother-in-law’s culinary masterpiece) while Asian males are incorrigible sadists and hopeless geeks. An Asian girl — or boy for that matter — would likely come away from the movie thinking that anything is preferable to marrying an Asian and suffering unrelenting misery.

All this is made worse by the fact that the movie is directed by an Asian American though Tan’s book was adapted for the screen by a veteran Hollywood screenwriter who probably had much to do with making the changes calculated to make the movie play to white audiences (like making the miserable tightwad, a White in the book, an Asian). Putting Wayne Wang’s name on the thing as director says it’s okay to look at Asians as a race of women without men.

Despite all their rhetoric about being solicitous of the Asian image, neither Amy Tan nor Wayne Wang evidences concern about the stereotypes that Asian men must .suffer day in and day out. They’ve been turned into willing accomplices by the lure of Hollywood success.

Then there’s David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly which not only won a Tony but will be turned into a movie. The main characters are a French diplomat and a Chinese male spy who becomes a drag queen to seduce the diplomat and steal state secrets. Don’t ask me how the couple manage to be lovers for some ridiculous number of years. I know that this is supposed to be based on a real-life incident. I know that Hwang’s artistic rationalization for writing the play is to show that racial preconceptions hurt both sides. But there’s no escaping the play’s visceral impact. The handsome, slightly effeminate John Lone playing a devious and cunning drag queen not only undercuts Asian masculinity on a fundamental level, it reinforces the image of Asians as being so debased that we would do anything for a cause.

Rising Sun, starring Sean Connery and the charismatic Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa, provided a badly needed relief from the usually sorry portrayal of Asian males but was booed by some on the ground that it made Japanese seem too threatening.

Amy Tan and David Henry Hwang have rubber stamped the most egregiously offensive exploitation of Asian stereotypes in recent memory and we’re supposed to applaud just because they’re Asian. Yet we’re supposed to rise up in outrage over a movie like Rising Sun which treated Asian males with far more dignity than either of the so-called Asian American works. At least Rising Sun portrayed Asian men as effective, fun-loving and virile.

Rather than blindly applauding the likes of David Henry Hwang, Amy Tan and Wayne Wang just because they’re Asians, no matter what kind of offensive drivel they produce, let’s ask ourselves this question: How would we feel about their works if they had been written and produced by non-Asians? By that test we would be outraged. Should our response be different because Asians are the nominal creative forces behind them? On the contrary, I think we should be even more outraged that they’ve let themselves be used as proxies for the white imagination. Asian artists who let their imaginations get coopted that way are the saddest victims of racial strereotyping.