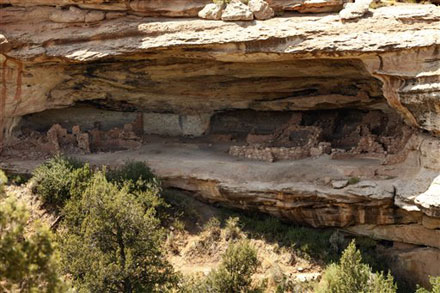

High above the spiky sandstone spine known as Comb Ridge that snakes for 120 miles through the desert, archaeologist Winston Hurst treads carefully through a cave of ruins.

The sun blazes down, illuminating the ghostly dwellings carved into the alcoves more than a thousand years ago. To a stranger the pre-Columbian pueblo ruins seem breathtakingly intact — walls and windows and rooms still standing, storage chambers for corn strewn with thousand-year-old cobs, large stone grinding slabs and brightly colored pottery sherds scattered throughout.

The archaeologist sees only destruction.

Driving to the ridge down a bumpy desert road across a plain dotted with sagebrush, cottonwood and pinon, Hurst points to trashed “pit houses” dating from 500-700 A.D. — distinctive mounds in the brush, where looters have dug for the ancient Indian tools, pottery, jewelry and blankets traditionally buried with the dead.

In the cave, more desecration. Centuries-old rock petroglyphs depicting animals and people and tools are daubed with modern graffiti, from “H.E.E.” (the Hyde Exploration Expedition of 1892) to “Liz Jones, age 8, 2003.”

A few yards away, another, more telling signature: the archeologist’s own name, scratched into a rock when he was a 12-year-old boy and scrambling through ruins collecting arrowheads was a way of life.

The name is barely legible, gouged out by local artifact hunters who consider Hurst a turncoat. He shakes his head sadly. “I have been where they are … they have not been where I am,” says Hurst, 62, who as a teen, once stored his prized collection of ancient bones next to his mother’s canned peaches.

Growing up, one of Hurst’s closest friends was Jim Redd, who went on to become a beloved rural doctor. But their friendship faltered over artifacts. While Redd continued digging and collecting, Hurst became a champion of preservation, passionate about the need to leave pieces of the past in place.

“He couldn’t stand my sermonizing and I felt sick every time he showed me his latest collection,” Hurst says, though Redd remained his doctor.

Their two worlds collided this summer when 150 federal agents swooped into the region, arresting 26 people at gunpoint and charging them with looting Indian graves and stealing priceless archaeological treasures from public and tribal lands.

Seventeen of those arrested, most of them handcuffed and shackled, were from Blanding, including some of the town’s most prominent citizens: Harold Lyman, 78, grandson of the pioneering Mormon family that founded the town. David Lacy, 55, high school math teacher and brother of the county sheriff.

And 60-year-old Jim Redd, along with his wife and adult daughter.

The next day, the doctor drove to a pond on his property and killed himself by carbon monoxide poisoning. Another defendant, from Santa Fe, N.M., shot himself a week later.

The suicides horrified this town of about 4,000 with many bitterly blaming the government. More than a thousand people attended Redd’s funeral, even as the mayor denounced the FBI and Bureau of Land Management agents as “storm troopers” and the sheriff called for a formal investigation.

For many, the recriminations and grief masked more complicated questions — questions that have dogged the town for decades.

Here, in one of the country’s richest archaeological regions — where the ruins of ancient pueblos are tucked into towering sandstone cliffs and pottery, arrowheads and Clovis points are scattered above old trails — how should the past be protected and preserved? And in a place where “pot-hunting” has been a way of life for more than a century, who, if anyone, owns that past?

___

“Chindi” is how the Navajo describe the evil spirits they believe inhabit the bones and possessions of the dead — spirits that can poison a person or place if they are disturbed, spirits that some believe have poisoned this town.

Even Navajo patients who revered Redd spoke sorrowfully of how the chindi had ruined his life. And, though many voiced unhappiness at what they saw as the heavy-handedness of the arrests, there was little doubt the Redds— who had been charged with grave digging in the past — knew they were breaking the law. After the raids, authorities removed two moving vans full of artifacts from the Redd home. Redd’s wife, Jeanne, was sentenced to three years probation and a $2,000 fine after pleading guilty to seven counts of trafficking in stolen artifacts and theft of artifacts on government and tribal lands.

It is a felony to take any artifact, even a fragment, from public land. There are also laws requiring the repatriation of human remains and sacred ceremonial artifacts to tribes.

But laws can’t change attitudes or traditions, or make much of a dent in the thriving black market where prehistoric Indian artifacts can fetch hundreds of thousands of dollars. And in the vast cliffs and mesas of the Four Corners region, where Utah, Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico intersect, where a handful of rangers from the National Parks Service and the Bureau of Land Management oversee millions of acres, enforcement is practically impossible.

Archeologists like Hurst say it’s up to them to try and educate people, to change “hearts and minds.” But there are many who believe the arrests have only hardened the very hearts and minds that need to change.

“I’m not against them enforcing the laws, but why do they have to kill us at the same time,” says Austin Lyman, a case worker at the senior center, who has vehement opinions about the raids, and his own unique way of expressing them:

“Like Jackals from hell they came,

With bullet proof vests and guns,

They came to arrest old men.”

Lyman, a burly, ruddy-faced man of 62, penned “Paradise Has Been Raided Again” on June 10, the day of the raids. He reads it aloud, eyes burning, voice cracking with emotion.

Behind him, taped to a cabinet next to posters of Elvis, is a smiling picture of Redd, Lyman’s personal physician and one of his best friends. Three of Lyman’s brothers, Harold, Dale and Raymond, all in their 70s, were arrested, and Lyman is still bitter about a similar raid that targeted his father in 1986.

Lyman’s grandfather, Walter, founded the town in the early 1900s and the family name is one of the most respected in these parts. Harold, who volunteers at the local visitors center, was recently inducted into Utah’s Tourism Hall of Fame.

Growing up, Lyman said, collecting arrowheads was like collecting seashells and ancient pots were so numerous they were used for target practice. His brothers weren’t “hardened criminals or grave robbers,” Lyman says, “just harmless old men who like arrowheads.”

Prosecutors paint a far different picture, describing a tight-knit ring that plundered pristine archaeological sites, desecrated Indian graves and stole ancient artifacts, selling them to dealers and collectors connected to the network.

Authorities refuse to comment directly on the investigation, code-named “Cerberus Action” after the multi-headed dog in Greek mythology that guards the underworld. But court documents describe a 2½-year sting in which undercover informant Ted Gardiner, wearing wires and taking photographs, ingratiated himself into the network, spending more than $335,000 on Anasazi pottery, ceremonial masks, a buffalo headdress, jewelry and sandals associated with ancient burials.

With the FBI watching every move, Gardiner (identified only as “the source” in documents, though his identity is well known in town) infiltrated a secretive world of diggers and dealers who looted by moonlight or in camouflage, flew in small planes searching for ruins, and thought nothing of kicking out skeletons and skulls.

Gardiner, a well-connected Utah dealer who was paid $224,000 for his undercover work, visited the homes of suspects with wads of cash as well as wires. He paid David Lacy more than $11,000 for a digging stick, a turkey feather blanket, sandals dug from burial sites and a menstrual loincloth, among other items.

Lacy’s brother is San Juan County Sheriff Mike Lacy, a sturdy, fast-talking man of 60 who is so incensed about how the raids were handled — and about being kept in the dark — he has asked Utah senators Orrin Hatch and Robert Bennett for a formal investigation.

“This was the biggest grandstanding stunt I’ve ever seen in my life,” says Lacy, whose father was sheriff before him, and who personally knows most of those arrested.

Driving through town in his sheriff’s van, Lacy points to all that Blanding has done to preserve its archaeological heritage — the Edge of the Cedars Museum, filled with Indian artifacts and an excavated pre-Columbian ruin; the Four Corners Cultural Center, and its reproductions of a Navajo hogan, Ute tepee, and a pioneer log cabin; even the new hospital, which hosts a Native American healing center.

Lacy pulls up at his house, a modest Cape on a neat suburban road, and strides over to a small rise beneath an apricot and apple grove in his backyard.

“There are ruins buried here,” he says, gesturing at the ground. “There are ruins everywhere in Blanding. Anyone who owns a few acres owns a mound or a ruin.”

For now, Lacy has no interest in digging what is likely an ancient pit-house, though legally he is entitled to do so. Unlike many countries where antiquities belong to the state regardless of where they are found, in the United States artifacts belong to the owner if they are discovered on private land.

Lacy’s wife is a Shumway, a relative of the notorious Earl Shumway, who in the 1980s and 1990s bragged about ransacking thousands of sites, including graves — “Around here, it’s not a crime. It’s a way of life,” he famously said. Shumway was eventually convicted and sentenced to more than six years in jail, though only after he had informed on other pot-hunters, rounded up in a raid in 1986.

The combined effect of the two raids, says Lacy, is a community living in fear that innocent people will be locked up for owning a pot that has been in their family for generations.

“Blanding will never get over it,” the sheriff says. “And it’s not going to stop people collecting.”

___

Curator Marci Hadenfeldt strolls through the cool, softly lit floors of the Edge of the Cedars museum, past cases of exquisitely decorated pots, baskets, tools and jewelry — one of the largest collections of Anasazi artifacts in the Southwest.

Most displays have an official note identifying the artifact, describing where it was excavated, and the era it dates to. Hadenfeldt stops at the largest collection — shelves of ceramic pots, hundreds of them, dazzling in their colors, shapes and geometric designs. The note next to the case states “Provenience Unknown.”

Hadenfeldt sighs. Though the collection, much of it dug up illegally by Earl Shumway, is stunning, it is worthless in an archaeological sense.

“When things are looted you lose the context and the story of the piece in addition to the archaeological record,” Hadenfeldt says. “The items are lovely and we can conjecture about where they might have come from, but we can’t be sure.”

There are signs throughout the museum explaining the laws, exhorting visitors to be good cultural stewards by leaving artifacts in place, even small pieces they might stumble upon hiking. “This is not just a good thing to do,” the signs say, “it is the law.”

But it is impossible to police. Every so often the museum will receive a box of pottery pieces, along with a note of apology, in the mail — sherds collected by hikers who later have regrets. The gesture is useless, Hadenfeldt says. The damage was done when they were removed in the first place.

There are dozens more artifact collections around town — in private homes, in trading posts, and in a most unlikely looking log cabin on the outskirts of town.

Huck’s Museum and Trading Post is an astonishing place, its modest exterior hiding a vast trove of history and archaeology — rooms filled with arrowheads, thousands of them, metates, pots, atlatls, gourds, sandals, bone rings, beads, feathers, axes and jewelry.

“Huck” is Hugh Acton, stooped, whiskered and gravelly voiced, who jokes that at 81 he’s an artifact himself. He charges $5 for a tour, and then spends over an hour shuffling from one room to the next talking passionately about the pieces and how he acquired them.

Acton, who has been collecting all his life, says he does so out of a genuine love for the past, and a desire to share it with everyone. His artifacts came from legitimate collections and dealers, he says, and are not for sale. It is legal to own artifacts that have been in circulation for decades, before laws protecting them were passed.

Acton grows serious talking about the raids, which he said have made collectors and dealers so jittery that people are nervous about doing business as usual.

“It should cure people of digging,” Acton says, “but it won’t.”

At the Thin Bear Indian Arts trading post on the other side of town, Bob Hosler, 75, says the same thing. “It’s not moral to dig in graves, but you can find this damn stuff everywhere,” says Hosler, who claims to have once aimed a shotgun at pot-hunters digging on his land.

Hosler’s small, dark store is crammed with traditional Indian jewelry, arrowheads, baskets and pots. Some are ancient artifacts that he found on his property, he says. Others he has owned for years.

Like other traders, Hosler believes illegal digging will persist because it’s ingrained in the local culture and because the market is so lucrative. High-end galleries in Santa Fe can sell Navajo blankets and kachina dolls for hundreds of thousands of dollars. There are dozens of sites selling Indian artifacts on the Internet. As recently as May, Sothebys auctioned a classic Navajo blanket for $53,000.

The raids, which he calls “government entrapment of old men,” have only cemented attitudes about pot-hunting and about federal interference in local affairs, Hosler says.

As he vents, a couple of women walk in carrying trays of handmade beaded jewelry. They are members of the Benally family, from the Najavo reservation south of Blanding and they have been trading with Hosler for years. They have nothing but kind words for the dealer, who greets them in Navajo and asks after their families.

But they have very different views about the raids.

“It’s wrong,” says Melinda Cottman, 38. “We were taught not to touch artifacts, not to dig, to leave the dead alone. To do otherwise is to bring sickness and bad luck. To bring the chindi.”

___

“We all own the past,” argues Ramona Morris, spokeswoman for the Antique Tribal Art Dealers Association, which represents collectors and dealers around the country. “It is our collective heritage.”

Morris, a collector from Virginia, says the raids sent a chill through association members, many of whom have been dealing in artifacts for decades. Though they can claim legitimate title and scrupulously follow the laws, she says, they are worried about having to suddenly prove they are legal. And they fear the entire industry has been branded as unscrupulous, and criminal.

She describes collectors as “caretakers … trying to preserve and show the value of other people’s cultures.”

But many Navajo, who believe that for over a century their ancestors’ graves have been looted for private gain, have a very different view.

In his gallery in Bluff, 25 miles south of Blanding, Curtis Yanito delicately polishes a traditional, handcrafted cedar flute as he ponders the past and the people who want to own it.

Soft-spoken and deliberate, the 42-year-old Navajo artist has no sympathy for pot-hunters or collectors or even archeologists. He is impatient with those who argue that digging used to be legal; slavery was once legal, too, he says.

Yanito’s gallery is filled with beautifully crafted contemporary pieces — traditional blankets and bowls, sand paintings and jewelry, most of it handmade by Yanito’s extended family. There are no prehistoric pots or arrowheads. Yanito wouldn’t dream of entering a ruin.

“The cliff dwellings are ALL grave sites and everyone knows that,” he says. “The dead should be left alone.”

Yanito, son of a medicine man, grew up in a traditional hogan on the nearby reservation where he still lives. He knows the history of the region as well as anyone, how “pot-hunting” began in the late 1800s when a Colorado rancher discovered the Anasazi ruins in Mesa Verde.

He knows the “white-man laws” designed to protect native artifacts and burials — from the 1906 Antiquities Act which introduced penalties for people taking or destroying artifacts without permission, to the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), which called for the return of ancestral remains, burial objects and other “cultural items.”

And he knows the objections of collectors and dealers — that NAGPRA is too vague, that its penalties are too great (first-time violators face up to a year in prison and a $100,000 fine), that any tribe can claim an object is sacred and demand it back.

Such arguments strike Yanito as hollow. He believes that all ancient artifacts, ruins and burials — including those on private lands — should be left undisturbed. He points to the example of a well-known Santa Fe dealer, Forrest Fenn, who owns and is privately excavating an entire pueblo settlement on his land. (Fenn’s home was raided as part of the investigation, though he has not been charged.)

Why should he be entitled to these things, Yanito asks. Who gives him that right?

Why should someone think it is OK to dig up and sell an ancient menstrual cloth, he continues, his voice filled with disgust. “That is pure evil.”

Yanito picks up the flute and starts playing, a slow, haunting, Navajo tune about living in harmony with nature, about living in harmony with each other. There is no harmony when there is looting, Yanito says, after he finishes. There is no harmony in Blanding these days.

Outside, the sun sets over the sagebrush plains of the reservation that stretches out along the San Juan River, and over the jagged sandstone cliffs that soar into the sky.

Those cliffs own the past, Yanito says, glancing up at them as he locks up his store. And that is where the past belongs.