|

GOLDSEA |

ASIAMS.NET |

ASIAN AMERICAN PERSONALITIES

THE 130 MOST INSPIRING ASIAN AMERICANS

OF ALL TIME

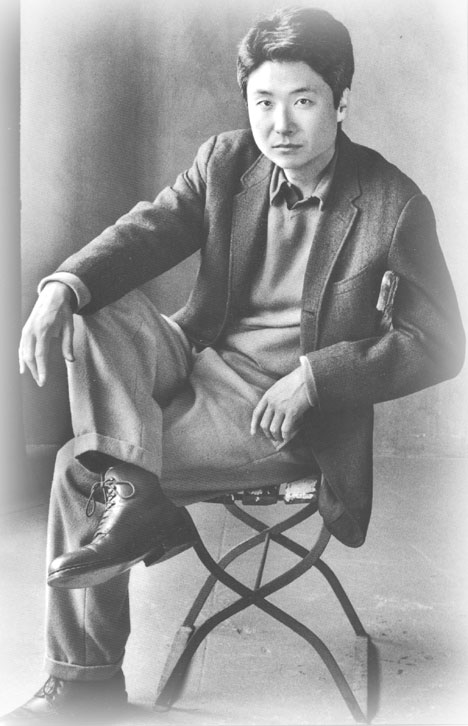

Chang-rae Lee:

An Artist of the Floating World ust because Chang-rae Lee parlayed a Yale B.A. in English lit into a full professorship on Princeton's Council of the Humanities and Program in Creative Writing, doesn't mean he's a lapdog of the New Yorker set any more than, say, Frank Chin is the mad dog of Asian American letters. Lee is a prodigy who committed early and worked hard enough to score a PEN/Hemingway Award and American Book Award at the age of 29 for his first novel Native Speaker (Riverhead 1995). The literary establishment's warm embrace more than offset the charge that it fantasized the immigrant experience. After all, at a time when Coreans were seen as liquor store owners squeezing profits by rudely overcharging welfare recipients, getting any kind of recognition for the Corean American perspective was no mean feat. ust because Chang-rae Lee parlayed a Yale B.A. in English lit into a full professorship on Princeton's Council of the Humanities and Program in Creative Writing, doesn't mean he's a lapdog of the New Yorker set any more than, say, Frank Chin is the mad dog of Asian American letters. Lee is a prodigy who committed early and worked hard enough to score a PEN/Hemingway Award and American Book Award at the age of 29 for his first novel Native Speaker (Riverhead 1995). The literary establishment's warm embrace more than offset the charge that it fantasized the immigrant experience. After all, at a time when Coreans were seen as liquor store owners squeezing profits by rudely overcharging welfare recipients, getting any kind of recognition for the Corean American perspective was no mean feat.

And who could quibble with a second novel (A Gesture Life, Riverhead, 2000) that secured his place as his generation's Most Promising Asian American Writer? A few critics muttered about its bloodlessness but far fewer dared suggest that its exquisite stasis was a pale imitation of Kazuo Ishiguro's Remains of the Day (Henry Holt, 1989) or that it loaded arcane guilt trips on Asian men or that it sidestepped the harsh realities of Asian life in America.

With his third (Aloft, Riverhead 2004) Lee opens himself to the accusation of having cut the tethers to his deepest material and sails off into the airy stuff of suburban angst. Ishiguro fans would argue that if a Nagasaki-born Japanese Englishman can write faultlessly about the regrets of an Oxfordshire butler, then Seoul-born Lee can write about an Italian American Long Island contractor full of the failings most amusingly lampooned in thick Tom Wolfe novels.

Unfortunately, the first-person narrator of Aloft sounds like a literature professor (...which I'd bring back and duly serve to her, as the saying goes, with love and squalor.") rather than a man used to being heard over the din of jackhammers and concrete-mixers, inviting suspicions that Lee has ditched authenticity to homestead the new dustbowl of erudite voices lamenting the rigors of life in the illusory heart of American life.

Lee could have spared himself grief by the simple expedient of narrating Jerry Battle's ruminations in the third person, freeing himself to indulge his taste for literary tributes and fluorishes. Instead Lee struggles to fit his windy elegies to old-millennium suburban life into a hardhat's jaded gaze. The resulting verbal flights whiplash into literary space without plausible grounding in calloused flesh and tired blood:

Just to the south, on the baseball diamond -- our people's pattern supreme -- the local Little League game is entering the late innings, the baby-blue-shirted players positioned straightaway and shallow, in the bleachers their parents only appearing to sit church-quiet and still, the sole perceivable movement a bounding golden-haired dog tracking down a Frisbee in deep, deep centerfield. Nor can we picture a prematurely-retired contractor describing a call to his son with such philosophical rambling: One of our usual goodbyes, from the thin catalogue of father-son biddings, thinner still for the time of life and circumstance and then, of course, for the players involved, who have never transgressed the terms of engagement, who have never even ridden the line. I then walked into the hangar office with a light-on-my-feet feeling, not like a giddiness or anxiety but an unnerving sense of being dangerously unmoored, as though I were some astronaut creeping out into the grand maw of space, eternities roiling in the background, with too much slack in my measly little line. And it occurred to me that in this new millennial life of instant and ubiquitous connections, you don't in fact communicate so much as leave messages for one another, these odd improvisational performances, often sorry bits and samplings of ourselves that can't help but seem out of context. Poet-contractors undoubtedly exist, but having one for a narrator overlays the novel with an uneasy consciousness of Chang-rae Lee the Princeton writing professor. At a time when even pop culture is venturing into the margins of American life to mine experiences that haven't been blended, homogenized and distilled into sitcoms, Lee's narrator returns to the mythical center to excavate the detritus of suburban existence like some archaelogist from a remote future.

CONTINUED BELOW

I used to have neighbors down the street named Guggenheimer, George and Janine, a couple right around my age with a bunch of kids and longhaired dogs. They moved in just after Daisy died and lived there for eight or so years. From my point of view they were a happy, sprawly, boisterous lot, always playing lawn darts or Wiffle ball, the hounds racing around and almost knocking over the kids, George and Janine constantly attending to their house (the same ranch model as mine), either sweeping up or landscaping. Whatever once quickened the scene is long dead in this sunset cruise of a narrative, but it does burnish Kodak moments with the golden sheen of cultural ideals shared and fleetingly realized in passing. This tour-de-force of kitsch may be taken for a palpation of the faint pulse of the American Dream and won't enhance Lee's bona fides as a novelist with an authentic voice. The best that can be said on that score is that Aloft doesn't pretend to depict Asian Americans except at a resigned remove, through the benign eyes of a man with an ex-wife and a son-in-law who both happen to be Corean American: People say that Asians don't show as much feeling as whites or blacks or Hispanics, and maybe on average that's not completely untrue, but I'll say, too, from my long if narrow experience (and I'm sure zero expertise), that the ones I've known and raised and loved have been each completely a surprise in their emotive characters, confounding me no end. Authenticity is a mantra for a writer struggling to find a transom ajar. For one who has spent his adulthood in the embrace of those who subscribe to print-quality lives, it's an inconvenient commodity, one that interferes with the pedagogical values of craft, manners and cultural lineage. The literary elegy that began in ancient Greece and echoes today between Princeton's Gothic towers and battlements doesn't invite the voice of a Corean American immigrant with too strident an identity. Chang-rae Lee buries it under the supremely detached gaze of a generic American who has fought life to a standoff and is ambivalent about a second chance. Battle's son-in-law Paul Pyun is the author's effort at relegating his Asian identity to a conscientious, academic footnote.

"People often ask me if [Native Speaker] is an autobiographical book," Chang-rae Lee said in staking a claim to the immigrant experience. "And of course from the facts it's not autobiographical. But the feeling of being both within and without at the same moment, that is a feeling that was very strong in me."

That sense of duality seems to have faded in his new incarnation as an anointed literary figure. "As I've grown up, clearly the culture has changed a bit, and I've changed, and I don't have that sense any more -- but maybe I should," he has confessed. PAGE 2 Page 1 | 2

Back To Main Page

|

|

|

|

Aloft, Chang-rae Lee's third novel, examines the American experience through the eyes of a retired Italian American Long Island contractor. |

“The feeling of being both within and without at the same moment, that is a feeling that was very strong in me.” |

CONTACT US

|

ADVERTISING INFO

© 1996-2013 Asian Media Group Inc

No part of the contents of this site may be reproduced without prior written permission.

|

ust because Chang-rae Lee parlayed a Yale B.A. in English lit into a full professorship on Princeton's Council of the Humanities and Program in Creative Writing, doesn't mean he's a lapdog of the New Yorker set any more than, say, Frank Chin is the mad dog of Asian American letters. Lee is a prodigy who committed early and worked hard enough to score a PEN/Hemingway Award and American Book Award at the age of 29 for his first novel Native Speaker (Riverhead 1995). The literary establishment's warm embrace more than offset the charge that it fantasized the immigrant experience. After all, at a time when Coreans were seen as liquor store owners squeezing profits by rudely overcharging welfare recipients, getting any kind of recognition for the Corean American perspective was no mean feat.

ust because Chang-rae Lee parlayed a Yale B.A. in English lit into a full professorship on Princeton's Council of the Humanities and Program in Creative Writing, doesn't mean he's a lapdog of the New Yorker set any more than, say, Frank Chin is the mad dog of Asian American letters. Lee is a prodigy who committed early and worked hard enough to score a PEN/Hemingway Award and American Book Award at the age of 29 for his first novel Native Speaker (Riverhead 1995). The literary establishment's warm embrace more than offset the charge that it fantasized the immigrant experience. After all, at a time when Coreans were seen as liquor store owners squeezing profits by rudely overcharging welfare recipients, getting any kind of recognition for the Corean American perspective was no mean feat.