hree months each summer Dr. Chi Huang walks to work. His commute begins at one in the morning. He traverses the streets of La Paz, Bolivia, elevation 12,000 feet. He can see his breath.

hree months each summer Dr. Chi Huang walks to work. His commute begins at one in the morning. He traverses the streets of La Paz, Bolivia, elevation 12,000 feet. He can see his breath.

Huang then descends a ladder bolted to a bridge. The bricks of that bridge are smeared with feces. They discourage the predators of La Paz from also descending. At the base of the bridge is a creek, but it isn't a clear mountain brook. It's an open sewer. And its smell can overwhelm.

“The sewer smells like a dumpster in the summer,” says Huang. “When I pass a dumpster in Boston, it provokes memories of Bolivia. In that sewer, the stink of the feces and the urine mix with the odor of paint thinner. My wife becomes sick after an hour.”

Huang descends into the sewer because that's where some of his patients live, the patients he calls “my children.” Street children of La Paz, they shelter under bridges and cardboard and form makeshift, shifting families. In the sewer, they sniff paint thinner and cut themselves to ease their misery.

“Ninety-eight percent of the children sniff paint thinner to numb themselves,” says Huang. “It ages them. 13 year olds look like theyŐre 18. It also does irreversible brain damage; cerebellar damage develops after 6 months. Some can't even complete a full sentence. But when you sniff paint thinner, you feel warm.”

Cutting themselves is another way to muffle pain.

“In the United States, it's usually girls that cut themselves,” says Huang, “but in Bolivia, both girls and boys cut. Some will have more than 100 razor blade cuts. They cut their wrists and their thighs. Cutters are usually mentally, sexually, and physically abused, with a hatred of their bodies. They carry a tension, an angst, and cutting releases that tension. ItŐs a defense mechanism that keeps them from killing themselves.”

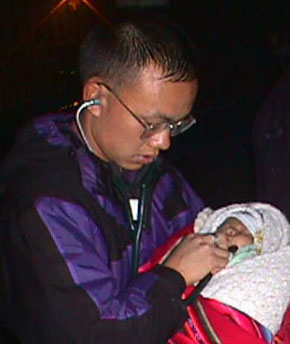

In the sewer, Huang treats sexually transmitted diseases. He tends to tooth infections, cuts and minor fractures. He also addresses mental health issues. He is frequently shocked by what remains undamaged in the children.

“I don't know how can they even believe in a God, but they do,” says Huang. “And they have a strong sense of right and wrong. They know it's wrong to beat an elderly woman for her money, but when they are hungry and cold, they must choose. They would rather beat an elderly man. Once, when I dropped about $8 in bolivianos out of my pocket, they picked it up and returned it to me. I've learned that it's not black and white in the sewer and the streets. It's made up of grays.”

The 33-year-old Huang graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1998. He is the Medical Director of the Pediatrics Inpatient Service at Boston Medical Center. He is familiar with the most modern and effective treatments. But when one plies medicine in a sewer, and when one seeks to treat more than symptoms, the interventions aren't merely medical.

“We often play soccer,” says Huang. “Because of the cold, the children stay up all night.”

Soccer is more than a way of staying warm. It's a way to be with the children.

“You can't tell them what to do after being there for a mere month,” says Huang. “They must know you.”

Huang is not content with engendering relationships and treating infected wounds. He intends to bring as many children as possible out of the sewer. To this end, he and his wife are adopting a girl from La Paz and they have opened an orphanage (http://www.bolivianstreetchildren.org and http://www.bolivianstreetchildren.org) that houses 11 former street boys.

“They live a structured life,” he says. “They awake at seven in the morning, make their beds, and shower. There is a communal breakfast and chores. Then they go to an in-house classroom from nine to 12. After lunch, it's public school until six.”

Public schools in Bolivia are not up the standards of American public schools, so Huang wants to provide superior schooling. PAGE 2