A little-known episode in China’s struggle to modernize has been brought to life by Liel Leibovitz in Fortunate Sons (W.W. Norton). The book traces 120 boys sent by the Qing Court in the early 1870s to study and live in New England in hopes of seeding China’s efforts to modernize.

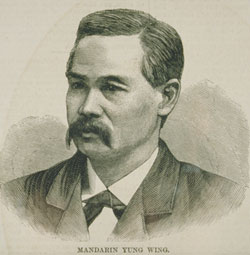

The history of these students and their contribution to their nation’s emergence from centuries of intellectual torpor makes for fascinating reading. Even more fascinating is the story of Yung Wing, the man who originated the plan to organize China’s first experiment with foreign study. Yung was a man of remarkable character, energy and intellect who figured colorfully in the earliest personal interactions between China and the U.S.

Yung Wing was born in Macau to a poor family in 1828. When he was seven his parents enrolled him in a small English missionary school in hopes that learning English may improve his prospects in life. It led to an opportunity for Yung, at age 19, to follow an American priest to the U.S. in 1847. After only three years of preparatory study at the Monson Academy in Connecticut, Yung enrolled at Yale. Remarkably, the student from China distinguished himself among his 98 American classmates by winning two first prizes in English composition.

On October 30, 1852 Yung Wing became a naturalized American citizen. In 1854 he became the first Chinese to graduate from Yale. Already conceived in his mind was a plan to help advance China.

“Before the close of my last year in college I had already sketched out what I should do,” Yung wrote in his autobiography My Life in China and in America (Henry Holt & Co., 1909). “I was determined that the rising generation of China should enjoy the same educational advantages that I had enjoyed; that through western education China might be regenerated, become enlightened and powerful. To accomplish that object became the guiding star of my ambition. Towards such a goal, I directed all my mental resources and energy. Through thick and thin, and the vicissitudes of a checkered life from 1854 to 1872, I labored and waited for its consummation.”

After finishing his studies, Yung Wing returned to Qing Dynasty China via an arduous 5-month voyage around the Cape of Good Hope. Soon after his return to Canton (Guangzhou) Yung came upon a blood-soaked street piled high with beheaded corpses. They were among 75,000 people slaughtered by a corrupt viceroy as part of a plan to extort bribes from his subjects.

The young and idealistic Yung supported himself as an interpreter, customs translator, trading firm clerk, law apprentice and tea trading agent. He turned down opportunities to enrich himself in various ways in order to preserve his integrity and reputation for such time as he might have an opportunity to advance his plan to persuade the government to send Chinese youths to study in the United States.

Two incidents showed the extent to which his seven years in America had awakened a sense of personal dignity that was deeply outraged by the contempt that many foreigners displayed toward Chinese in their own country. The first incident involved a drunk American sailor snatching a lantern from Yung’s servant, then attempting to deliver a kick to Yung himself. The kick didn’t land, but Yung learned the name of the drunk and wrote a note to his captain. It produced an apology from the drunk.

The second incident ended in violence:

The Scotchman, after the incident, did not appear in public for a whole week. I was told he had shut himself up in his room to give his wound time to heal, but the reason he did not care to show himself was more on account of being whipped by a little Chinaman in a public manner; for the affair, unpleasant and unfortunate as it was, created quite a sensation in the settlement. It was the chief topic of conversation for a short time among foreigners, while among the Chinese I was looked upon with great respect, for since the foreign settlement on extra-territorial basis was established close to the city of Shanghai, no Chinese within its jurisdiction had ever been known to have the courage and pluck to defend his rights, point blank, when they had been violated or trampled upon by a foreigner. Their meek and mild disposition had allowed personal insults and affronts to pass unresented and unchallenged, which naturally had the tendency to encourage arrogance and insolence on the part of ignorant foreigners. The time will soon come, however, when the people of China will be so educated and enlightened as to know what their rights are, public and private, and to have the moral courage to assert and defend them whenever they are invaded.

The incident earned Yung a wide reputation. Other incidents served to play up his unusual command of the English language. The death of a beloved senior partner in a British trading firm in Shanghai prompted local Chinese merchants to draw up an epigraph. The surviving partners wanted a translation that would properly capture its precise tone. They asked two translators to produce competing versions — Yung and the British interpreter in the British Consulate General. After deliberation they chose Yung’s.

A few months later a great flood in the Yellow River caused many Chinese to become homeless and wander into Shanghai as refugees. A local official sought out Yung’s help in drafting an appeal to the city’s foreign community. Yung created a circular that quickly raised $20,000 (equivalent to about $1.5 mil. today).

In 1863 Yung’s growing reputation led him to be summoned by Zeng Guofan, by then imperial China’s most powerful official. Zeng had risen from an obscure minor court official after raising a disciplined army from his native Hunan that routed the Taiping Rebels and ultimately ended their rebellion, the most serious threat ever faced by the Qing Dynasty. By the time the two met Zeng was able to command as much of China’s resources as he wanted. Yung recognized the meeting as the opportunity he had been long awaiting.

Astutely, Yung refrained from proposing the project dearest to his heart. Instead he made a proposal that was more likely to resonate with Zeng’s focus on strengthening China’s military capabilities — import a master machine shop with which China could build other machine shops to produce modern firearms and other military equipment. Zeng promptly dispatched Yung with the equivalent of about $3.4 mil. of today’s dollars to travel to Europe and the United States to secure the necessary equipment. Through an overseas mission lasting over a year Yung procured the machinery. It became the heart of China’s imperial armory.

It wasn’t until 1871 that Yung finally won the Qing court’s approval for his plan to organize a Chinese Educational Mission. It called for 120 boys between the ages of 12 and 15 to study in New England for a period of 15 years at a total budget of $1.5 mil (equivalent to about $45 mil 2011 dollars). They were sent in groups of 30 students per year beginning in 1872. Yung preceded the first group by a month to arrange for schools and families to host the boys. This was the realization of the dream that Yung had conceived two decades earlier.

“The Chinese Educational Scheme is another example of the realities that came out of my day dreams a year before I graduated,” he would write later. “So was my marrying an American wife.”

That wife was Mary Kellogg whom Yung wed in 1876. They had two sons — Morrison Brown Yung, born near the end of that year, and Bartlett Golden Yung, born two years later. That same year, at Yale’s centennial commencement, Yung Wing was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree. He also persuaded the Qing court to let him build a large, handsome building in Hartford, Connecticut at a cost of $50,000 (about $1.7 mil. today) to serve as the headquarters of the Chinese Educational Mission.

A shadow was cast over this happy period by the anti-Chinese violence spreading in California as labor leader Denis Kearney and other racist demagogues began blaming Chinese immigration for a shortage of jobs and low wages. Long before the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in May of 1882 conservative Chinese officials began calling for an end to the Educational Mission on the ground that life in the U.S. was corrupting the students and making them unfit for service to their nation. Despite efforts by Yung to counter such charges, the Qing court recalled the 112 remaining students.

In 1895 China’s humiliating defeat to Japan in a brief war over Korea prompted the Qing court to recall Yung with a view toward soliciting proposals for strengthening the country. Yung drew up plans to add armored warships to China’s navy, to finance a modern military and to create a central Bank of China. All fell through due to court intrigue and graft by competing interests.

In 1898 the Empress Dowager mounted a coup against the reform-minded Guangxu Emperor and decapitated many key reformers. A price of $70,000 was placed on Yung’s head, forcing him to flee Shanghai for Hong Kong. From there he applied for a visa to return to the United States. A 1902 letter from Secretary of State John Sherman informed Yung that his citizenship had been revoked and that he would not be allowed to return. This decision was based on the Scott Act of 1888 which prohibited reentry for Chinese who had left the U.S. The prohibition was permanently renewed in 1902. (The Chinese Exclusion Act and its progeny were repealed in 1943 by the Magnuson Act.)

Thanks to the help of friends Yung Wing was able to sneak back into the U.S. just in time to see his younger son Bartlett graduate from Yale. He spent his remaining years in Hartford. His autobiography was published in 1909. He died in poverty in 1912. He is buried at Cedar Hill Cemetery outside Hartford, Connecticut. He is remembered by a public elementary school, P.S. 124, named in his honor at 40 Division St. in New York’s Chinatown. A Yung Wing School also exists in Zhuhai in southern China.