There’s a lesson or two buried in the news stories about the rampaging black cop Christopher Dorner, elderly Korean American shooter Chung Kim, and recognition by Michigan of a day honoring Japanese American internment resister Fred Korematsu.

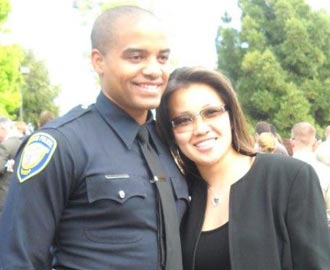

These disparate stories speak in part to the question of how assertive we Asian Americans should be. Are we too averse to conflict as Dorner suggested in his rambling manifesto? Would Monica Quan and her fiance still be alive if her father Randal — who had represented Dorner in the Board of Rights appeal of his termination from the LAPD — had been white?

Here’s the single paragraph Dorner devoted to his assessment of Asian American officers in the long manifesto he mailed to the media after killing Monica, her black fiance and another police officer:

Those Asian officers who stand by and observe everything I previously mentioned other officers participate in on a daily basis but you say nothing, stand for nothing and protect nothing. Why? Because of your usual saying, “I—don’t like conflict.” You are a high value target as well.

No one knows the feverish turning of gears in Dorner’s head when he chose to murder Monica and her fiance. All we know is that he chose them as the first assassination targets of his revenge rampage simply for being related to the attorney who represented him in his failed bid to win back the job from which he was terminated. The termination was for allegedly fabricating the allegation that he had seen his female superior kick a mentally ill detainee several times, including once on the face.

Dorner’s choice of his first victims was full of irony.

As the first Chinese American to attain the rank of captain in the LAPD, Monica’s father Randal Quan probably suffered at least as much racial prejudice during his quarter century on the force as Dorner claims to have suffered during his four years. As Dorner’s attorney, Quan was probably the single person most invested in Dorner’s fight to win back his job. Quan exhibited none of the anti-black prejudice Dorner complains of in his manifesto. Not only was he representing a black former officer who was apparently very unpopular in the LAPD, Quan’s daughter was engaged to Keith Lawrence who happens to be black.

Yet Dorner chose to punish Quan by killing his daughter and Lawrence — neither of whom had any apparent connection with him — to kick off his campaign to seek revenge on those who had wronged him. The only explanation apparent in his manifesto is his reference to his characterization of Asians as being averse to conflict.

Dorner’s murder of Monica and her fiance tends to invalidate his assessment of Asian Americans. On another level, we already know that he is merely echoing the characterization others have applied to Asian Americans, including some Asian Americans themselves.

As it happens ample rebuttals to that accusation were supplied by other news stories running simultaneously with those about Dorner’s endgame.

One was Michigan’s recent decision to join California in observing January 30 as Fred Korematsu Day in honor of the Japanese American who chose to defy the federal government rather than submit to Executive Order 9066 sending Japanese Americans to internment camps. With the help of Ernest Besig, the determined ACLU director of northern California, Korematsu took his fight to the Supreme Court three times. Only on his third attempt was he successful in getting the high court to acknowledge, on November 10, 1983, that the internment order had been unconstitutional at the time it was issued in January 1942.

On September 23, 2010 California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed a bill designating January 30 as the Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution. It was observed for the first time in 2011. Other memorials have been erected to honor Korematsu.

Of course most of the wrongs we Asian Americans fight don’t touch on issues of constitutional significance or ones in which we are representing an entire segment of the American population. Usually they involve dealing with people who disrespect us, often because of our race, facing us with the stark choice of quietly submitting to some indignity or turning it into an open, sometimes physical, conflict in which there is rarely a winner.

That was the kind of situation faced by Chung Kim, a 75-year-old Korean American man living alone in Dallas. The upstairs neighbors — a black couple in their early 30s with 5 small children — had the habit of letting their small dog use their balcony as its toilet. The pee and poop dropped onto Kim’s patio and in front of his door. For nearly a year Kim tried to get the neighbors to end the practice and the condo association to take action. He failed.

When it happened again last week Kim is accused of taking action. The police say he shot and killed both adults. Kim says the male neighbor put a gun to his head and he merely reacted in self-defense. The gun has been sent out for analysis. Meanwhile Kim is in jail facing murder charges and the five orphaned children have been sent to live with relatives.

Kim’s plight illustrates, perhaps, that an elderly Asian who speaks halting English sometimes has trouble commanding respect in American society. It’s hard to imagine the same kind of thing happening to an elderly white person. This tragedy — as well as other unfortunate situations involving younger, more articulate Asian Americans —show that we share a burden imposed by others’ perceptions about our race, no matter how inaccurate.

Monica Quan appears to have been a victim of Dorner’s perception that her father Randal was somehow complicit in his plight because Asians don’t like conflict. Fred Korematsu and over a hundred thousand Japanese Americans spent two years in internment camps due perhaps to the assumption that they were unlikely to speak out even against such a gross violation of their rights.

Such misperceptions continue to breed confrontations, some of which end tragically. Each such confrontation helps dispel the false perception that confuses Asian forbearance and respect for order with an inability to engage in open conflict. Ironically, Dorner’s manifesto points out the folly that some people — especially racists — have of confusing kindness and manners with weakness. If nothing else, Dorner has joined countless Asians in helping illustrate the dangers of making that mistake.