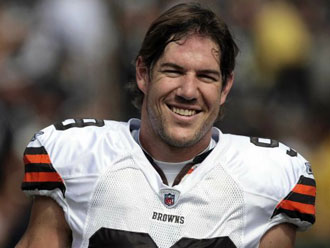

Cleveland Browns linebacker Scott Fujita has drawn on his Japanese American adoptive family’s internment experience in an essay on acceptance of gay marriage published Sunday in the New York Times.

“They will learn that their great-grandmother Lillie delivered a son, their Grandpa Rod, in a Japanese-American relocation camp during World War II,” Fujita writes, referring to his adoptive father Rodney Fujita. “Initially, they might be shocked that this is part of America’s past. But I’ll be able to tell them, ‘I think a lesson was learned from that experience, and it won’t happen again.’”

“They will learn that couples of different races, like their grandparents, were once denied the right to marry,” he continues, referring to his father’s marriage to his mother Helen, a caucasian woman. “But at least I’ll be able to say, ‘Thanks to a Virginia couple named Richard and Mildred Loving, things are better now.’”

In its 1967 decision in Loving v. Virginia the US Supreme Court struck down the anti-miscegenations laws on the books of many states, including California. Until that decision interracial couples in California were forced to travel to more tolerant states like Washington to marry.

“I support marriage equality for so many reasons: my father’s experience in an internment camp and the racial intolerance his family experienced during and after the war, the gay friends I have who are really not all that different from me, and also because of a story I read a few years back about a woman who was denied the right to visit her partner of 15 years when she was stuck in a hospital bed,” Fujita explains in his essay.

“My belief is rooted in a childhood nurtured by a Christian message of love, compassion and acceptance. It’s grounded in the fact that I was adopted and know there are thousands of children institutionalized in various foster programs, in desperate need of permanent, safe and loving homes, but living in states that refuse to allow unmarried couples, including gays and lesbians, to adopt because they consider them not fit to be parents.”

Fujita wrote the essay as part of his longstanding leadership in efforts to fight homophobia in sports. It was published on the eve of an upcoming US Supreme Court ruling on the constitutionality of California’s Proposition 8 which overrode a state law and banned gay marriage.

“On Tuesday, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments on California’s Proposition 8, which banned same-sex marriage,” Fujita’s essay continues. “I agree with the lower courts that said Proposition 8 violated the constitutional rights of gay men and women without any evidence-based rationale for doing so, and I, along with other professional athletes, signed my name to a brief sent to the court stressing the importance of marriage equality. Now the Supreme Court — like a referee in a football game — has the opportunity to simply enforce the rules as written. And I’m confident the justices will.”

The essay opens by explaining the awkwardness Fujita feels in trying to explain to his three young daughters why a lesbian couple with whom he and his wife are friendly are unable to get married.

“Years ago, my wife and I became friendly with a young woman whose teenage brother committed suicide after coming out to an unsuspecting and unsupportive father. This woman explained that her father was a football guy, a “man’s man” — whatever that means. She challenged me to speak up for her lost brother because, as she said, the only way to change the heart and mind of someone like her father was for him to hear that people he admires would embrace someone like his son.”

In conclusion, Fujita writes, “I don’t ever want to explain to my daughters that some ‘versions’ of love are viewed as “less than” others. I’m not prepared to answer that kind of question.

“Instead, in just a few short years, and in the same way we now sometimes ask the previous generation, I hope my daughters will ask me: ‘What was all the fuss about back then?’ I’m looking forward to hearing that question.”

Scott Anthony Fujita born on April 28, 1979 in Ventura, California. He was only six weeks old when his birth mother gave him up for adoption to Helen and Rodney Fujita, a third generation Japanese American who had been born inside the Gila River internment camp in Arizona.

Scott grew up amid the Fujita family’s observances of Japanese cultural traditions like Shogatsu (Japanese New Year) and Kodomo-no-hi (Children’s Day). But the part of Japanese American heritage that seems to have left the deepest impression on Scott is the injustice of internment and the courage and fortitude with which his grandparents coped with the ordeal.

Fujita told ESPN that the toughest person he knows is his grandmother Lillie and recounted an incident that happened to her a few days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. As Lillie was crossing the street in Berkeley a white female student ran up to her and screamed in her face, “You little Jap, why don’t you go back home!”

“I’m an American too … and a better one than you are!” shouted back Lillie who is unusually petite, even for a Japanese woman of her generation. Fujita recalled that at his wedding reception he got down on his knees to dance with his grandma only to find that he was still too tall.

Two months later when President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 the Fujita’s were among 120,000 Japanese Americans who were ultimately relocated to 10 internment camps. The family lost hundreds of acres of farmland in Ventura County which today would be worth tens of millions of dollars. Scott’s grandfather Nagao, Lillie’s husband, enlisted and fought with the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team in Italy. The unit went on to become the most decorated in US military history thanks to daring battlefield exploits that also cost them the highest casualty rate in the US military during World War II. After returning from the war, Nagao Fujita studied law and ultimately become one of the first bilingual attorneys on the West Coast.

These stories about the Fujita family’s tribulations and triumphs during an age of intense racial prejudice shaped Scott’s views on any form of prejudice or discrimination. Even today he is angered that the subject of Japanese American internment was never discussed in school history classes.

“I’m so far removed from the topic, but when I think about it, it makes me bitter and angry,” he says. ”The thing is, I’ve never heard a single hint of negativity in my grandmother’s voice. Part of the culture is to make the best of everything, to not feel sorry for yourself and to move on — I’m honored to have been able to absorb that into my own life.”

Scott’s own life seems to have been relatively sheltered from direct racial prejudice.

“American, Japanese, to me he’s always just been my son,” Rodney told ESPN of his experience raising a blond, blue-eyed boy as his son.

After playing football at Oxnard’s Rio Mesa High School Scott walked on at Cal. He suffered a neck surgery that nearly ended his football career, but managed a comeback and made the all-Academic Pac-10 team while graduating with a degree in political science and a masters in education.

Fujita was picked in the 5th round of the 2002 NFL draft by the before the Kansas City Chiefs. He was traded to Dallas where he played during the 2005 season before signing with the New Orleans Saints in 2006 as the team’s first free agent after their return to New Orleans. He became the team’s defensive captain in 2007. On February 7, 2010 Fujita was part of the Saints team that won Super Bowl XLIV over the Indianapolis Colts.

Fujita just completed his third season with the Cleveland Browns under a 3-year, $14-mil. contract. During the 2010 season he was second in the team in tackles and sacks. During the 2012 season he was initially suspended for three games for his alleged participation in the Saint’s bounty scandal but he was ultimately cleared of any wrongdoing at the end of the 2012 season.

In the off-season Fujita — 6-5, 250-lbs — lives with his wife and three daughters at their home in Carmel Valley, California. He has become an outspoken supporter of abortion rights, gay rights, adoption and wetlands preservation, among other causes. In 2009 his charitable activities earned him the Saints Man of the Year award. He is also an ambassador for Athlete Ally, an organization that fights homophobia in sports.