Shigeru Miyamoto's Mario Is Game World's Enduring Brand

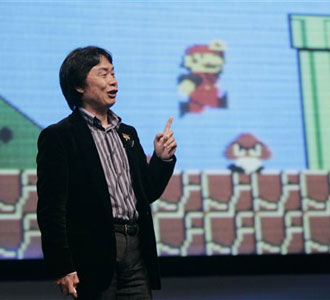

Figure of Fun: Shigeru Miyamoto's Mario is the digital world's grey eminence.

You might call him the Mickey Mouse of video games. He’s reminiscent of a doughnut, round and sweet and comforting. He’s also a vessel, devoid of a real personality so you can live vicariously through him.

Mario, the pot-bellied Italian plumber with a penchant for rescuing princesses, collecting golden coins and gobbling magic mushrooms, has been around for nearly three decades. And even though he hasn’t changed much, the latest game he stars in, the newly released “The New Super Mario Bros. Wii” ($50), is one of the holiday season’s top titles.

Created by Japanese game designer Shigeru Miyamoto, Mario is a recognizable character even to people who don’t play video games. He pops up in Halloween costumes — blue overalls, red hat, gut and all — as does his brother Luigi. Mario has been in cartoons and movies (though some were best forgotten), and he graces oodles of official and unofficial Mario merchandise.

“I like him. I like him a lot. He has a cool mustache,” says Colin Gaul, 9, from Portland, Ore. “He is awesome because he is brave and he’s been on a lot of adventures. And his favorite color is red and mine is too.”

Colin first played a Mario game when he was 5, on Nintendo Co.‘s handheld Game Boy system. On the Wii, Colin has played “Super Paper Mario” and “Super Smash Bros. Brawl,” which features a cavalcade of Nintendo characters duking it out.

But Colin wasn’t even born when Super Mario emerged.

First called Jumpman, the character debuted in 1981 in the arcade game “Donkey Kong,” in which Jumpman had to save a damsel from a big ape. His first job was carpentry, but later he became a plumber, and in many games he travels up and down in a world of underground pipes.

In the mid-1980s, Nintendo and Mario helped save the U.S. video game industry, which was on the verge of imploding after early popularity. Terrible games — most infamously “E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial” — had flooded the market, and “people didn’t realize that video games were a burgeoning industry,” says Scott Steinberg, lead video game analyst at Digitaltrends.com. “They thought it was a fad.”

It wasn’t. With the launch of the Nintendo Entertainment System in 1985, which in the U.S. came bundled with “Super Mario Bros.,” video games became a household phenomenon. Nintendo sold 60 million of the consoles, often called the NES.

In 2008, Americans spent more than $21 billion on video game systems, software and accessories, according to the NPD Group. Even with a recession and industry slump this year, the number will likely be close to that, with a good chunk of the money going to Nintendo. The company has been able to stay profitable, thanks largely to its Wii and the handheld DS being the world’s top-selling gaming systems.

In all, Nintendo has sold more than 222 million games in its Super Mario franchise. There are more than 100 games, for various gaming systems, in which Mario is the primary character, and many more in which he makes appearances.

The Japanese company’s creation of an Italian character is now video game folklore. In his book “Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered the World,” David Sheff wrote that Mario was named after Nintendo’s U.S. landlord, who was demanding back rent from the company’s fledgling U.S. arm. Nintendo now won’t confirm or deny the story.

Perhaps more important is that many of the features that define Mario came about from shortcuts that were needed in the early days of video game design, when arcade units had puny computing power and displayed few colors. He wears a hat, for example, so that his creators didn’t have to render hair. His super-sized mustache easily hides facial expressions — which even now remain difficult to program into video games.

“The reason he continues to be so popular is that Mario is basically an everyman,” Steinberg says. “Behind those bushy eyebrows, jolly belly, is gamers themselves. Short, balding, goofy — how many gamers does that describe?”

Miyamoto has called Mario a “convenient tool” who can be used with a range of games, whether they’re racing titles such as “Mario Kart” or take place in the magical world of the Mushroom Kingdom where Mario fights to save Princess Peach.

The new game is a throwback to Mario games of the 1980s and ’90s, played out in two dimensions rather than three. The characters mostly move left to right — jumping on platforms, stomping enemies and ducking through pipes into hidden areas.

Reviews have been mixed. The Associated Press, for example, found the game may disappoint fans looking for innovation but would probably “deliver plenty of newcomers to the cult of Mario.”

Miyamoto says he hopes the latest installment attracts both Mario experts and people new to the game. It has a multiplayer option, a first for a Mario game, that lets four people play alongside one another, with better players helping less experienced ones.

Ian Bogost, a professor who studies video games at Georgia Tech, says Mario’s enduring popularity is not merely about nostalgia for the 1980s.

“Mario is more like a brand,” he says. “You drink Coke or buy a Chevrolet not simply because of nostalgia, but because it continues to represent something to you that you value.”

And in Mario’s case, the brand stands for good, clean fun. Colin’s mother, Ninou Gaul, 33, who played Mario games as a kid, still occasionally picks up the Wii controller.

“It’s timeless,” she says, “and the level of violence is nothing I would object to.”

11/18/2009 2:59 PM BARBARA ORTUTAY, AP Technology Writer NEW YORK

Shigeru Miyamoto, Nintendo Corp's top game designer, gives a keynote address as the game Mario Brothers plays in background at the 2007 Game Developer Conference in San Francisco. (AP Photo/Paul Sakuma)