The Evolution of an Asian American

As with all painful transitions, it begins with denial. Willful oblivion. Blissful ignorance. Whatever you want to call it. As kids we'd rather not know or believe that we are to live out our lives being immutably different from the majority. Most of us take that first scary step down the evolutionary path only because we're pushed.

As best as I can reconstruct it, my first step occurred in the seventh grade. The occasion was a birthday party. I had known Steve since kindergarten and had been invited to every other birthday party. I simply assumed it was a mistake, an oversight by his mother, that I hadn't been invited.

I showed up at the party bearing a gift. The smile that froze on his mother's face when she answered the door, the stiff and slow way she moved aside to let me enter, stays etched in my memory like a slo-mo replay of a quarterback whiplashing from a late hit. This is a woman who had been welcoming me into her home for ten years. I entered and took in the scene. It should have dawned on me that my failure to receive an invitation had been no accident. I determinedly refused to see the situation.

Girls had been invited. Something like a tea dance was in progress. By what I now know to have been the social norms of that time and place (east Texas circa the early 80s), there could have been no place for me in that gathering as there was no Asian girl in the social circle from which Steve's mom had drawn up the guest list. The clarity of hindsight wasn't available to me that day as I registered impressions like the broken shards of a stained-glass window I had never seen intact. On that day I was not even ready to imagine the scene that must have taken place during one of Steve's family dinners before the invites had been mailed. If so, I might have pictured Steve questioning his mother's decision but being silenced by his parents' united front. They must have been determined to make Steve shed an embarrassing old friendship that should have been phased out with sipper cups and chewable vitamins.

"But don't you see, Steve, Johnny just wouldn't fit in!" I might have imagined his mother insisting.

No such insight entered my brain that day as I sat alone sipping Hawaiian punch while seven matched sets of white adolescents took their first baby steps down the shady lane to the exclusive clubs on the north side of town. Had I been further down my own evolutionary road, I would have pictured Steve's face as he contemplated the harsh social consequences his parents were warning against if he persisted in keeping me in his circle of friends. What could an ordinary boy of thirteen say against the weight of such dire consequence? Steve was no larger-than-life hero like you see on TV movies, sticking up for the ideals of racial equality and friendship in the face of adult pressure.

On that afternoon I felt Steve trying to avoid my eyes as he pushed his partner like a broomstick around the living room. Not that I was exactly trying to meet his. I was alternating between a feeling of invisibility and the desire for it, but I didn't want to lend any more reality to the awful suspicions that must have taken root in my subconscious. I couldn't work up the nerve to take those half dozen steps toward the front door. That would have been tantamount to telling everyone -- worst of all my own quaking little heart -- that I had been deliberately excluded, and even worse, that I was someone who knew that his presence had not been wanted. And why. No, I was far from being ready that day to accept even that most obvious and basic fact of my immutable difference from all my childhood friends.

But, as I said, the seeds of awareness had taken root somewhere deep down because when I did finally work up the nerve to unfreeze my body and walk out of Steve's house, I spent an hour wandering around in the hills so I wouldn't have to go home early and provide an explanation to my parents. I don't recall thinking about anything in particular, but I do recall feeling deeply ashamed as though I had done something wrong. When I did slip into the house, I went straight up to my room, then spent a good half hour staring at that odd face in the mirror, hardly daring to breath. I never did return to Steve's house again.

That rude awakening to my racial identity changed me practically overnight. I became less spontaneous with old friends. I began putting distance between us, finding reasons to spend more time alone. And each day of my life seemed fraught with complications. Perhaps all adolescents go through a similar process. What I remember with total clarity is that the world quickly became a darker place, one filled with the possibilities for intense pain.

As painful as that day was, it was just the first step down the evolutionary road to becoming an Asian American. I would take many more steps over the next fifteen years to arrive at a happy place on that road. None proved quite as painful as that first youthful moment of mute anguish.

My next big step came a couple years later when an Asian girl (whom I will call Mariel) transferred to our school. Looking recently through my high school yearbook, I see that she was pretty, with a brilliant dimpled smile. I recall her as having been intelligent and full of spunk and determination. She was the daughter of an engineering professor at a local university. What I recall most vividly was my own dread of being thrust together with her solely on the basis of our race. It was one thing for me to recognize that I was different from my friends; it was quite another for me to be automatically paired with a stranger on that basis. My racial identity was too new and fragile to allow me to feel romantic interest in an Asian girl. It would have felt wrong to me, like taking comfort in a shared stigma.

Steve again played a role in my evolution. Maybe because of what had happened at his birthday party, he had begun taking an active interest in finding me a girlfriend and was delighted when Mariel transferred to our school. Steve kept asking what I thought of her. My noncommittal responses were calculated to hide the panic I felt at the thought of being thrust together with her. Steve seemed to take them as signs of interest. I later learned that his girlfriend had become friends with Mariel and had extracted from her signs of interest in me. Steve pushed me to agree to a double date. I was wounded by his casual assumption that race was such an important trait as to assure romantic attraction within a sampling of two. He and his girlfriend made me feel I would be doing them a huge personal favor by going out with Mariel.

Mariel showed no trace of misgivings about being on a date with the only other Asian in the grade. She made determined smalltalk. She was a trooper. I was as charming as a cardboard cutout. So conscious was I of our having been thrust together on the basis of race that I couldn't enjoy myself with an intelligent beauty who should have been attractive to any guy. I recall feeling hugely relieved as we dropped her off at home. That was the last time Steve and his girlfriend tried to play cupid with Mariel and me.

Strangely, that awkward date set off an infatuation that lasted throughout my high school years. I may not have been secure enough to enjoy Mariel as a date, but my sense of identity had awakened enough for me to admire her from afar. My feelings were a mix of empathy, curiosity, a physical yearning and a kind of brotherly pride. I always took pleasure in hearing how well she was doing in her classes and on the tennis and soccer teams. After a time I could chat with her between classes without feeling unduly self-conscious. By graduation we were close enough that I filled up an entire page of her yearbook with a goofy cartoon. In mine she had written, in part, "In our next lifetime we should be much better friends..." It was something she might have written on a lot of yearbooks, but I took it to heart as a personal reproach.

That sense of regret colored my view of the bewildering number of Asians I encountered in my first weeks in college. They represented for me an opportunity to connect at long last with my identity. To my dismay the other Asians seemed to see me as just another student and didn't reciprocate my eagerness to befriend them. Before long I got wind that the others in the dorm considered me a banana, a thoroughly whitewashed Asian. I came off as trying to patronize other Asians instead of trying to relate to each as an individual, I was told by a sympathetic Asian guy on my floor. I took this as a rejection that reinforced my longstanding insecurities about my identity. I retreated from other Asians and from my crusade to embrace my identity. I sought out the comforting familiarity of Whites. They may have seen me as a racial minority, but at least they weren't alienated by my friendly overtures.

My entire first year was tinged with the bitter disappointment of my failure to make the long-anticipated Asian connection. In my sophomore year I met Dan, a Japanese American who had grown up in the Midwest. I confided to him my sense of alienation from other Asian Americans. He agreed that it was tricky for Asians who had grown up in white areas to fit in with those from the big coastal cities. "It's like they envy us for being so easy with Whites," Dan told me, "but they look down on us because they assume we have no pride in being Asian." That summed up our predicament, but didn't make it any easier to accept. Over time we bananas came together to form our own little clique. We even had our little jokes about the "FOBs". We poked fun at their clothes, their haircuts, their speech patterns. Cultivating a sense of superiority felt better than feeling like outcasts.

Toward the end of my sophomore year I was cramming for midterms at my favorite reading room of the research library. I noticed a pretty Asian girl studying at a nearby table. She was madly highlighting texts with a yellow marker while fiddling with her hair. Our concentration was broken by the raucous voices of frat rats joining a friend who had been studying at another table. They were talking in that peculiarly abrasive voice that only a group of frat boys could use in a library reading room. One or two frat boys were like mice but get three or more together and they were honor bound to disturb the peace.

Within a few minutes it became clear that they had no intention of respecting the rights of others in that reading room. It was also clear that none of the other dozen or so students were interested in speaking out. The Asian girl kept glancing at the frat rats with obvious annoyance. Just as I was making up my mind to get up and ask them to keep it down, she slapped the table with her book and glared at them. They were momentarily surprised into silence. Naturally they then decided that their collective manhoods were threatened by this gutsy girl and began slapping the table with their own books while staring at her.

"Can you go play outside?" the girl said in exasperation. I almost winced at her thick accent. It sounded like, "Can you go pray outside?" It was guaranteed to provoke more mockery from the frat boys. "Why don't you go pray outside with us?" one of them said, crudely mimicking her accent.

That set me off. I jumped to my feet and addressd the frat boys with a string of obscenities. I followed that up with an invitation for them either to go outside and play with me or shut the f*** up and let everyone study. They were stunned into silence. After a few minutes they gathered their things and left, muttering snidely by way of salvaging their pride.

I don't recall how much longer we studied there, but as I was gathering my things to leave I noticed the pretty Asian girl getting up to leave as well. She pulled up alongside and gave me a smile. "Thank you."

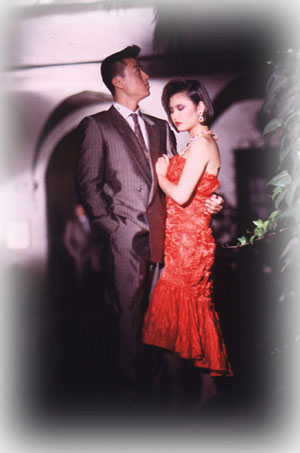

That was the start of a relationship that continues to this day, twelve years later. Leah is now my wife and her accent has faded over the years, to my regret. During the first few years I was endlessly charmed by everything remotely Asian about her. You might even say I had an Asian fetish. She personally disabused me of the many illusions I had had about what it was to be an Asian. I suppose I helped her see that even the most "whitewashed" Asian was subject to the same prejudices in American society. In many ways, we became Asian Americans together, each coming from opposite directions and meeting somewhere in the middle.

For the first several years of our relationship we tacitly assumed that the best of what we shared owed to being Asians. Our love of Asian travel destinations, foods, arts and aesthetics took up most of our leisure time. On the other side, we felt our minority status was the source of the negatives in our lives like workplace biases, encounters with racists and the stereotypes that make the American media an unreliable source of entertainment. Our lives could only improve if we were living as members of an Asian majority, we postulated. When I was approached about an Asia posting, we jumped at the chance. The job would give us a great income, fringe benefits and the advantages of living in a modern, vibrant Asian city. Best of all, we would escape the drawbacks of being members of a minority group.

At first we delighted in the experience of being Asians in an Asian land. We saw charm and welcome everywhere. We could walk through any door along a busy street and find a meal that seemed cooked especially to our liking. We could stroll for hours without encountering a curious or hostile stare. We never had to wonder whether we had wandered into the "wrong" section of town or if any bit of unpleasantness contained a racial component. We expected four years of unmitigated bliss. Instead we found ourselves taking the final step in our evolution as Asian Americans.

The first thing we began to miss were the infrastructural details to which we had never given much thought while living in the States: broad streets, spacious parking lots, efficient freeways, drive-thru everything. Then we became aware how judgemental the people were about everything. They seemed to attach signficance to every detail of what we wore, ate, drank, said or did. Bit by bit we came to see that being of the same race didn't spare us from the subtle and complex set of prejudices reserved for people not cut from precisely the same cloth. Before a year was out, we felt as victimized by prejudice as we had in the states. The fact that the prejudice was dished out by people who looked superficially like us made it no easier to take. The sense of immense freedom and acceptance that had once filled were taken from us by this judgemental pettiness and bewildering prejudices. Long before we returned to the States, Leah and I had become as united by our American attitudes as we had once been by our shared Asian heritages.

My evolution as an Asian American continues to this day. Lately it has become a process of seeing the many ways in which we Asian Americans can contribute to making this country a place of even greater spiritual freedom for people of all races. Now that I know what is mine, I am determined to make it better for me and all my countrymen.