Nobel-prize winning MIT neuroscience professor Susumu Tonegawa has devised a technique to create false memories in mice to show that recollections of events are highly malleable.

The aim of the experiment was to show that a mouse’s memory of a safe chamber could be made to conflate with that of a different chamber in which it received an electrical shock.

Tonegawa’s team began by introducing a mouse into a chamber that was devoid of any painful or unpleasant experiences. During the mouse’s stay in that chamber the team used a genetic technique to label the brain cells into which the memory of the chamber was stored.

The next day the mouse was placed in a second, completely different chamber where it was given a series of electrical shocks to the feet. During that unpleasant experience Tonegawa’s team shone light into the portion of the mouse’s brain in which was stored the memory of the first chamber in order to implicate that memory with the shocks.

Later when the mouse was returned to the first, safe chamber, it froze in fear, suggesting that its memory of that chamber had become altered so that it remembered receiving a shock there.

“The process of memory is nothing like a tape recording,” said the study’s co-first author Steve Ramirez. “It’s really malleable and susceptible to the incorporation of new information.”

Understanding how memories are formed and altered, the team hopes, will lead to new strategies for treating everything from lost memories to ways to modify the quality of memories in ways that may cure memory-related dementia.

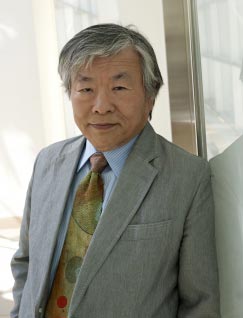

Susumu Tonegawa, 72, is a native of Nagoya, Japan. After receiving his bachelors degree from Kyoto University in 1963, he moved to the US to earn his doctorate at UC San Diego. Following post-doctoral work at San Diego’s Salk Institute, Tonegawa moved to Switzerland to work at the Basel Institute of Immunology.

Basel was where Tonegawa conducted the immunology experiments that won him the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1987. That seminal work showed that though the human body has fewer than 30,000 genes, genetic material rearranges itself to form millions of different types of antibodies, far more than had been previously suspected.

In 1981 Tonegawa became a professor at MIT where he founded and directed what is today the Picower Institute for Learning and Memory. He is a member of the Scientific Board of Governors at The Scripps Research Institute. He is currently the director of the RIKEN-MIT Center for Neural Circuit Genetics at MIT where he heads up a full research laboratory. As of April 1, 2009 he began serving simultaneously as director of the RIKEN Brain Science Institute in Wako, Japan.

Tonegawa’s work on the mechanisms of memory appears to date to the suicide of his son Satto, an MIT freshman, in October of 2011.