Kita represents a new kind of artist born for success in the age of global multimedia deals. Their stock in trade is attitude, visual style and exhibitionistic displays of primal urges. Their genius lies in perpetually remaking themselves to stay just far enough ahead of the social change curve to provoke without alienating. This kind of chameleon must be tough enough to rip out his own quivering innards for the cameras. Their real medium is the mass media, with their own voracious appetite for cleavage and confessions. Top multimedia artists, like Madonna and Prince, know instinctively what will set the media salivating and just how much raw meat to throw at them to keep them hanging around.

Such artists also display a cool, precocious head for business. Kita admits he used to dislike Prince but has lately come to appreciate his genius at building up his personality cult. He particularly admires the way Prince created Paisley Park, his own wholly owned record label, which enjoys the backing of a giant like Warner. Kita’s other role model is Madonna who he thinks is a less-than-beautiful girl with a mediocre voice who has managed to turn herself into a multimedia phenomenon.

“I’d like to do video,” Kita says of the offers he is getting, “play with the media, show my face to the world. That’s what Madonna is doing.” Which would he rather be — a male Madonna or an Asian Prince?

“I’d rather say,” answers Kita without missing a beat, “Madonna and Prince get stuck in an elevator and have incredible sex. For some strange reason Prince is the one who gets pregnant. I would be that child.” Then Kita orders linguini with clams.

Kita’s own ambitions for rock stardom are channeled through an entity called Ra Falcon whose offices are on Sunset Boulevard, right across the street from the Mondrian. Kita is founder and sole owner. He denies that the money for the venture came from his father, a successful construction contractor in Hawaii. When I press him, Kita says it came from investors who are “family friends”. A few days later, Kita tells me he got around a million dollars as a token of appreciation from a gang boss for whom he had performed an important service. What kind of favor could be worth a million dollars? Kita refuses to elaborate, hinting only that it involved helping the friend gain a crucial edge over a competitor.

Kita’s refusal to discuss particulars suggests the favor may have involved something illicit like drugs, white-slavery, maybe even murder-for-hire. When I suggest those possibilities, Kita keeps a poker face as he denies involvement with murder or drugs, seemingly conceding that it did have some connection with gang activities. Kita invested some of that mystery money in the Las Vegas house he sold recently for over a million, earning a big profit. That money seems to be one source of his startup capital.

Kita isn’t anxious to dispel the mystery about the source of his money. Whatever activities his finances may involve, there is no question Kita is very hands-on. Summer answers a call on the tiny Motorola portable she carries and hands it to Kita. With no apparent effort at disguising his conversation, Kita tells the caller that he is expecting some payments. He names several four- and five-figure sums. Loan-sharking occurs to me as another possible source of revenue. Kita’s preternaturally gentle, almost androgynous, voice and manners add to his air of danger and mystery. To look at him you could suspect he has ice water running in his veins. He never lets himself get excited enough to raise his voice, never lets himself become surprised enough to raise an eyebrow.

Even so there are times I am tempted to dismiss Kita as just another 25-year-old with a rich uncle and a smooth style. After all, he hasn’t even been signed by a major label. His first CD won’t even be released until January though Kita tells me “Desire” is getting air play in Europe, New York and Washington state.

The most distinguishing thing about Kita’s musical career is that he became something of a rock star in Guam at the age of 14. Admittedly Guam is a tiny place, but Kita says he enjoyed a lot of status and recognition there. At the age of 17, after his family had moved to the States, Kita played with three heavy metal bands in Orange County and L.A. Anticipating a big career ahead and wanting to keep artistic and financial control, he formed Ra Falcon four months earlier. Legendary rock producer/promoter Kim Fowley, associated with the likes of the Beatles, Helen Reddy, Guns-N-Roses and Motley Crue, is cited as a credential by Kita. In fact, Kita’s most significant step toward ultimate success may be having Fowley call him “the new pig on the block”. That kind of compliment doesn’t easily escape the lips of Kim Fowley, known for his offensive directness.

“You need cash to talk to me,” Fowley told Kita at their first meeting. Kita pulled out a hundred and layed it on Fowley’s hand. “Fowley has been screwed over a lot in the past,” explains Kita, “but we understand each other.” He has become a big fan of Fowley’s blunt ways and has retained him as a consultant, a big wheel in the star-making machinery. Another is the big-name publicist working to get Kita into European and American magazines. It is a measure of Kita’s ambition that he wants more than writeups in music magazines; he wants to be trumpeted in mass-market fashion and general-interest magazines.

Tomi Kita has three commodities to offer the media — looks, talent and most importantly, heavy-duty balls. As befits an aspiring rock star Kita is handsome verging on pretty. Judging by his CD and demo tape his singing voice is reminiscent of David Bowie and, on occasion, Eric Clapton. Kita writes all his own songs. The lyrics could maybe use a bit of discipline but they actually say something, a rare commodity in today’s music scene. One song even borrows from William Blake: “Tiger, Tiger burning bright/In the forest of the night.” Kita is proudest of his guitar playing. According to the credits he is a one-man production studio who arranged and mixed every cut. The only other credits go to a bass player and a drummer.

Ultimately what may raise Tomi Kita above a big field of hopefuls is his ballsy willingness to lay himself bare. With titles like “Masturbation” and “Loneliness is Fear by a Different Name”, his songs aren’t limited to pop sentiments. At the same time he doesn’t have the immature musician’s fear of the sentimental side, the eternal song themes. Some Kita songs are frankly about nostalgia and lost love. Sexuality is the unmistakeable current that drives his music and his ambition to become the male Madonna, but Tomi Kita’s ultimate talents are solid enough to withstand artistic scrutiny.

I find Kita appealing as a profile subject because his choice os ambition and lifestyle represents, to maybe too many talented Asian American males, the road not taken. Kita helps gut the stereotype. Where the stereotype has us being nerdy, he is convincingly ultra-hip, where it has us being respectable, he is proudly a freak, where we are supposed to be docile, he is clearly his own man, where we are supposed to be sexless, Kita is frankly oversexed and very much in command. At the moment he has three steady girlfriends, two of them models. His once-in-a-decade true love is a Swedish model. He tells me this in front of Summer, not unkindly, just matter-of-factly. She knows and accepts the fact that Kita doesn’t believe in monogamy. Kita tells me that he subscribes to the ancient Asian tradition in which men are allowed to keep as many wives and mistresses as they can afford.

Several times during our conversations, the subject of S&M and bondage comes up. Each time Kita leaves no doubt that in his bedroom scenarios the woman always plays the slave. He expresses the idea of male sexual dominance in the same gentle, cool way he might talk about breakfast. When posing with Summer at his photo session, gently but firmly Kita suggests that a good way to depict his philosophy toward women would be to have Summer fellating him while he grips her hair. We politely insist that Kita keep his pants on and that Summer’s lips stay a decent distance from his crotch.

Some could mistake Kita’s gentleness for some kind of new-age pacifism. In fact, Kita holds a third-degree black belt in Taekwondo. By age 16 he was already good enough to be instructing U.S. Marines on Guam. “They were all twice my size,” Kita says with an easy chuckle. “Any one of them might have kicked my ass but there’s the spiritual side of it.” Confident of his sexuality and physical prowess, Kita feels no urge to prove his masculinity with loud talk or aggressive behavior. His easy physical confidence adds to his aura of mystery and mastery.

No doubt his money adds something as well to that easy confidence. Few aspiring rock stars have the money to live for months on end in a hotel like the Mondrian or to drive a midnight black BMW with bulletproof windows which he had bought for $60,000 from a drug dealer or to keep a Sunset Boulevard office staffed with a receptionist, secretary and other retainers. As we walk two other members of Kita’s entourage seat themselves at the next table. One is a tall thin white male with long brown hair, another is a short-haired female. Neither are dressed for corporate success. Though they are sitting only a foot away, they studiously avoid looking our way. Our conversation is only interrupted when Summer hands Kita calls coming in over the tiny Motorola.

After we have been talking for some time Kita excuses himself to the men’s room. On the way back he stops at the grand piano and plays a few bars before padding back to our table. Giving off the vibes of some gentle free-spirit strewing daisies along his path, Kita stops to greet some people on his way back to the table.

A little-known episode in China’s struggle to modernize has been brought to life by Liel Leibovitz in Fortunate Sons (W.W. Norton). The book traces 120 boys sent by the Qing Court in the early 1870s to study and live in New England in hopes of seeding China’s efforts to modernize.

The history of these students and their contribution to their nation’s emergence from centuries of intellectual torpor makes for fascinating reading. Even more fascinating is the story of Yung Wing, the man who originated the plan to organize China’s first experiment with foreign study. Yung was a man of remarkable character, energy and intellect who figured colorfully in the earliest personal interactions between China and the U.S.

Yung Wing was born in Macau to a poor family in 1828. When he was seven his parents enrolled him in a small English missionary school in hopes that learning English may improve his prospects in life. It led to an opportunity for Yung, at age 19, to follow an American priest to the U.S. in 1847. After only three years of preparatory study at the Monson Academy in Connecticut, Yung enrolled at Yale. Remarkably, the student from China distinguished himself among his 98 American classmates by winning two first prizes in English composition.

On October 30, 1852 Yung Wing became a naturalized American citizen. In 1854 he became the first Chinese to graduate from Yale. Already conceived in his mind was a plan to help advance China.

“Before the close of my last year in college I had already sketched out what I should do,” Yung wrote in his autobiography My Life in China and in America (Henry Holt & Co., 1909). “I was determined that the rising generation of China should enjoy the same educational advantages that I had enjoyed; that through western education China might be regenerated, become enlightened and powerful. To accomplish that object became the guiding star of my ambition. Towards such a goal, I directed all my mental resources and energy. Through thick and thin, and the vicissitudes of a checkered life from 1854 to 1872, I labored and waited for its consummation.”

After finishing his studies, Yung Wing returned to Qing Dynasty China via an arduous 5-month voyage around the Cape of Good Hope. Soon after his return to Canton (Guangzhou) Yung came upon a blood-soaked street piled high with beheaded corpses. They were among 75,000 people slaughtered by a corrupt viceroy as part of a plan to extort bribes from his subjects.

On my return to headquarters, after my visit to the execution ground, I felt faint-hearted and depressed in spirit. I had no appetite for food, and when night came, I was too nervous for sleep. The scene I had looked upon during the day had stirred me up. I thought then that the Taiping rebels had ample grounds to justify their attempt to overthrow the Manchu régime. My sympathies were thoroughly enlisted in their favor and I thought seriously of making preparations to join the Taiping rebels, but upon a calmer reflection, I fell back on the original plan of doing my best to recover the Chinese language as fast as I possibly could and of following the logical course of things, in order to accomplish the object I had at heart.

The young and idealistic Yung supported himself as an interpreter, customs translator, trading firm clerk, law apprentice and tea trading agent. He turned down opportunities to enrich himself in various ways in order to preserve his integrity and reputation for such time as he might have an opportunity to advance his plan to persuade the government to send Chinese youths to study in the United States.

Two incidents showed the extent to which his seven years in America had awakened a sense of personal dignity that was deeply outraged by the contempt that many foreigners displayed toward Chinese in their own country. The first incident involved a drunk American sailor snatching a lantern from Yung’s servant, then attempting to deliver a kick to Yung himself. The kick didn’t land, but Yung learned the name of the drunk and wrote a note to his captain. It produced an apology from the drunk.

The second incident ended in violence:

A stalwart six-footer of a Scotchman happened to be standing behind me. He was not altogether a stranger to me, for I had met him in the streets several times. He began to tie a bunch of cotton balls to my queue, simply for a lark. But I caught him at it and in a pleasant way held it up and asked him to untie it. He folded his arms and drew himself straight up with a look of the utmost disdain and scorn. I at once took in the situation, and as my countenance sobered, I reiterated my demand to have the appendage taken off. All of a sudden, he thrust his fist against my mouth, without drawing any blood, however. Although he stood head and shoulders above me in height, yet I was not at all abashed or intimidated by his burly and contemptuous appearance. My dander was up and oblivious to all thoughts of our comparative size and strength, I struck him back in the identical place where he punched me, but my blow was a stinger and it went with lightening rapidity to the spot without giving him time to think. It drew blood in great profusion from lip and nose…

The Scotchman, after the incident, did not appear in public for a whole week. I was told he had shut himself up in his room to give his wound time to heal, but the reason he did not care to show himself was more on account of being whipped by a little Chinaman in a public manner; for the affair, unpleasant and unfortunate as it was, created quite a sensation in the settlement. It was the chief topic of conversation for a short time among foreigners, while among the Chinese I was looked upon with great respect, for since the foreign settlement on extra-territorial basis was established close to the city of Shanghai, no Chinese within its jurisdiction had ever been known to have the courage and pluck to defend his rights, point blank, when they had been violated or trampled upon by a foreigner. Their meek and mild disposition had allowed personal insults and affronts to pass unresented and unchallenged, which naturally had the tendency to encourage arrogance and insolence on the part of ignorant foreigners. The time will soon come, however, when the people of China will be so educated and enlightened as to know what their rights are, public and private, and to have the moral courage to assert and defend them whenever they are invaded.

The incident earned Yung a wide reputation. Other incidents served to play up his unusual command of the English language. The death of a beloved senior partner in a British trading firm in Shanghai prompted local Chinese merchants to draw up an epigraph. The surviving partners wanted a translation that would properly capture its precise tone. They asked two translators to produce competing versions — Yung and the British interpreter in the British Consulate General. After deliberation they chose Yung’s.

A few months later a great flood in the Yellow River caused many Chinese to become homeless and wander into Shanghai as refugees. A local official sought out Yung’s help in drafting an appeal to the city’s foreign community. Yung created a circular that quickly raised $20,000 (equivalent to about $1.5 mil. today).

In 1863 Yung’s growing reputation led him to be summoned by Zeng Guofan, by then imperial China’s most powerful official. Zeng had risen from an obscure minor court official after raising a disciplined army from his native Hunan that routed the Taiping Rebels and ultimately ended their rebellion, the most serious threat ever faced by the Qing Dynasty. By the time the two met Zeng was able to command as much of China’s resources as he wanted. Yung recognized the meeting as the opportunity he had been long awaiting.

Astutely, Yung refrained from proposing the project dearest to his heart. Instead he made a proposal that was more likely to resonate with Zeng’s focus on strengthening China’s military capabilities — import a master machine shop with which China could build other machine shops to produce modern firearms and other military equipment. Zeng promptly dispatched Yung with the equivalent of about $3.4 mil. of today’s dollars to travel to Europe and the United States to secure the necessary equipment. Through an overseas mission lasting over a year Yung procured the machinery. It became the heart of China’s imperial armory.

It wasn’t until 1871 that Yung finally won the Qing court’s approval for his plan to organize a Chinese Educational Mission. It called for 120 boys between the ages of 12 and 15 to study in New England for a period of 15 years at a total budget of $1.5 mil (equivalent to about $45 mil 2011 dollars). They were sent in groups of 30 students per year beginning in 1872. Yung preceded the first group by a month to arrange for schools and families to host the boys. This was the realization of the dream that Yung had conceived two decades earlier.

“The Chinese Educational Scheme is another example of the realities that came out of my day dreams a year before I graduated,” he would write later. “So was my marrying an American wife.”

That wife was Mary Kellogg whom Yung wed in 1876. They had two sons — Morrison Brown Yung, born near the end of that year, and Bartlett Golden Yung, born two years later. That same year, at Yale’s centennial commencement, Yung Wing was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree. He also persuaded the Qing court to let him build a large, handsome building in Hartford, Connecticut at a cost of $50,000 (about $1.7 mil. today) to serve as the headquarters of the Chinese Educational Mission.

A shadow was cast over this happy period by the anti-Chinese violence spreading in California as labor leader Denis Kearney and other racist demagogues began blaming Chinese immigration for a shortage of jobs and low wages. Long before the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in May of 1882 conservative Chinese officials began calling for an end to the Educational Mission on the ground that life in the U.S. was corrupting the students and making them unfit for service to their nation. Despite efforts by Yung to counter such charges, the Qing court recalled the 112 remaining students.

In 1895 China’s humiliating defeat to Japan in a brief war over Korea prompted the Qing court to recall Yung with a view toward soliciting proposals for strengthening the country. Yung drew up plans to add armored warships to China’s navy, to finance a modern military and to create a central Bank of China. All fell through due to court intrigue and graft by competing interests.

In 1898 the Empress Dowager mounted a coup against the reform-minded Guangxu Emperor and decapitated many key reformers. A price of $70,000 was placed on Yung’s head, forcing him to flee Shanghai for Hong Kong. From there he applied for a visa to return to the United States. A 1902 letter from Secretary of State John Sherman informed Yung that his citizenship had been revoked and that he would not be allowed to return. This decision was based on the Scott Act of 1888 which prohibited reentry for Chinese who had left the U.S. The prohibition was permanently renewed in 1902. (The Chinese Exclusion Act and its progeny were repealed in 1943 by the Magnuson Act.)

Thanks to the help of friends Yung Wing was able to sneak back into the U.S. just in time to see his younger son Bartlett graduate from Yale. He spent his remaining years in Hartford. His autobiography was published in 1909. He died in poverty in 1912. He is buried at Cedar Hill Cemetery outside Hartford, Connecticut. He is remembered by a public elementary school, P.S. 124, named in his honor at 40 Division St. in New York’s Chinatown. A Yung Wing School also exists in Zhuhai in southern China.

VFinity Inc CEO Shen Tong is a revolutionary, literally. As a leader of the student democracy movement that ended in the June 4, 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, Shen ran the movement’s underground radio station out of his Beijing University dorm room. He managed to flee China a few days later. Fifteen years later he founded a New York company that created the first web-native digital asset-management (DAM) system.

Becoming a tech entrepreneur may not sound like an extension of the revolutionary path. Shen would be the first to agree. Nevertheless he has imparted distinctly democratic touches to his firm’s VFinity 4.0 software. It prides itself as the only “web-managed” DAM platform, well suited for organizations inclined to give wide access to its videos, photos, audio files, graphics and text. The VFinity suite also lets media files be organized by “folksonomy” as well as by taxonomy. In other words, individual users have the power to assign their own labels and categories to content, while the administrator can impose a more formal classification scheme.

Shen Tong was the chief peace negotiator on behalf of the students who led the democracy movement that ended in the June 4, 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.

Twenty-two years after Tiananmen Shen Tong is a respected entrepreneur whose product is used by the likes of Bloomberg Multimedia and was recently included by Forrester Research among a handful of DAM segment leaders.

The path from a 20-year-old student leader to 42-year-old tech entrepreneur has had more twists and turns than the first halves of most entrepreneurial lives.

Shen Tong was born July 30, 1968, in Beijing. He enjoyed some acting success as a teen. A two-part made-for-TV movie in which he co-starred with actress Hu Zongwen won the 6th Fei Tian National Award in 1986, the same year he entered Beida, Beijing University.

By 1989 he had become one of about a half dozen highly visible student leaders leading peaceful marches for democracy across China. In fact, Shen was the chief negotiator in trying to secure a peaceful end to the demonstrations. By June 4, upwards of 100 million Chinese were rallying for democracy across the nation. That’s when tanks and guns were turned against the students crowding Tiananmen Square in the heart of Beijing. Shen was standing on Changan Avenue when the student next to him was shot and killed. He watched the streets erupted in gunfire and bodies began falling.

Fortunately for Shen, he had already been accepted to Brandeis University and had been issued a passport to study in the U.S. Six days after Tiananmen he went undisguised to the airport and boarded a flight for the United States though the state security police had put him on their most wanted list. Some have taken this as a sign that even many in China’s military had secretly been in sympathy with the democracy movement.

Inevitably, Shen’s first days in the U.S. — as were the first days of several other student leaders who managed to flee China — were taken up debriefing the western press about the Tiananmen Square massacre and the events leading up to it. That was followed by a decade of founding and leading the Democracy for China Fund with help from prominent Americans like Coretta Scott King, John Kerry, and Nancy Pelosi, among many other political leaders and activists.

Shen’s 1990 memoir Almost a Revolution was motivated as much by economic necessity as the desire to let the world know what had happened in China. His early freelance writing career included film reviews, essays, novels and movie scripts in English and in Chinese. Some of his writings were published in China under the pen name Rong Di.

Shen Tong studied biology at Brandeis University on a Wien Scholarship. He later pursued doctorate studies in political philosophy at Harvard and sociology at Boston University though he never completed his PhD work.

In 1992 Shen voluntarily returned to China on the strength of Deng Xiaoping’s pledge that China would welcome back student leaders who had left the country.

“Sure enough,” Shen recalled with an ironic smile, “they put me away.”

His 54 days in prison ended after presidential candidate Bill Clinton, the European governments, the Vatican and others focused the world’s attention on Shen’s plight.

“Did we make any difference?” Shen said to a Guardian reporter on the 20th anniversary of Tiananmen. “I’m not sure we did. It’s a huge price to pay: my youthful years, all of them. Second only to my own family, my beliefs remain probably the most important thing to me. But I don’t know what to do with them.”

In May 1993 Shen learned that China’s long arms could reach well beyond its borders. As the U.S. Congress was debating whether to renew China’s Most Favored Nation trading status, Shen was barred from giving a speech at the United Nations press club when UN General Secretary Boutros Boutros-Ghali caved in to pressure from China.

Shen eventually came to see technology as a tool with which to give people a voice, especially those living in China. He began shipping modems to China in the mid 1990s as the internet began to take root. In 2000 he moved to New York and started up a software company with his older sister Shen Qing. That company was the predecessor to VFinity. In 2004 Shen recruited a team of software engineers from MIT and elsewhere to create the first version of VFinity’s web-native DAM software. So far the startup has attracted $10 million in angel funding. In 2007 he achieved some industry recognition for his promotion of “Context Media” in a keynote speech he gave at a super session of National Association of Broadcasters in Las Vegas.

Ironically, Shen’s evolution from revolutionary to businessman is now bringing him into a profitable relationship with his native country. The organization that put on the 2008 Beijing Olympics was just one of many Chinese clients of VFinity’s DAM platform. These days Shen travels routinely to China on business. He’s still watched by state security officials, but he comes and goes without fear of losing his freedom.

Shen has stayed engaged with the arts as perhaps a surrogate form of revolution. In the early 1990s he worked with ABC News, the European cultural TV network Arte, and Jean-François Bizot’s Actuel magazine to produce Clandestins en Chine. The film premiered in a Paris theater and on Arte in 1992. Shen also starred in the 2000 film Out of Exile with co-star Sharif Atkins. During the mid-1990s his Boston-based foundation invested in various China ventures. One is B&B Media Production which created and produced several acclaimed TV programs for China, including the top-rated Tell It Like It Is. He has also sponsored a film festival. Since 2008 Shen has served on the board of Poets & Writers.

Shen Tong lives in SoHo with his wife, their two daughters and a son. His prominence on the arts scene and penchant for collecting Chinese art has given him a reputation as a hip and savvy art collector and investor.

“I have a normal life,” Shen said. “It sounds so basic, but among the exiles, that hasn’t been basic at all.”

If you’ve ever wondered how to do something, you’ve probably stumbled across Stephen Chao’s site. WonderHowTo.com is the internet’s compiler of how-to videos, claiming 10 million unique visitors each month, half of them from the U.S. It isn’t quite the numbers of, say, Fox TV, but given the precipitous decline of TV, the day isn’t far off when Chao’s do-it-yourselfer domain may reach par with Fox in eyeballs pulled.

As impressive as Chao’s site is — with an estimated 400,000 videos cataloged into 424 sub-categories — his claim to fame remains his exploits of the late 80s and early 90s while helping a nascent Fox network blossom to challenge ABC, CBS and NBC. For six years Chao ran himself ragged “with no bathroom break” to add freshness and excitement to Fox’s prime-time fare. He is credited with the hits America’s Most Wanted, Cops and Studs. Rupert Murdoch even elevated him to the post of Fox President after Barry Diller’s departure.

That title lasted 10 weeks until June of 1992 when Chao hired a male stripper to take the stage at a Fox management conference attended by then Defense Secretary Dick Cheney and his wife Lynne. Chao said he did it to illustrate his point that American TV is more skittish about nudity and sexuality than about violence. Murdoch, frankly, didn’t give a damn, and fired Chao on the spot.

That precipitated a seven-month period of intense navel-gazing that led to Chao’s compulsion to satisfy a burgeoning curiosity about McDonald’s, his favorite fast-food restaurant. He drove to the Redondo Beach store and signed on to flip burgers and assemble Egg McMuffins.

“It wasn’t the weirdest thing I had done in a relationship,” Chao says to explain why he wasn’t stopped by his live-in girlfriend (who became his wife, then his ex) with whom he had a two-year-old son.

Chao claims he isn’t “vain or insecure enough” to have worried about how this choice of employment might look to others. The restaurant was far enough from his Santa Monica/Westside orbit that he never encountered anyone he knew while working there. Word got out anyway. The McDonald’s episode fed into the edgy badboy legend that had arisen during Chao’s hair-on-fire days at Fox.

By early 1993 Stephen Chao formed a production company under his name and hunkered down in a nondescript Santa Monica office complex with a handful of staffers to develop projects for Murdoch’s Fox studios and for Q2, an offshoot of Barry Diller’s QVC home shopping network. Chao deems few of the projects to be worth remembering.

In April 1998 Chao returned to being a TV executive when Barry Diller bought USA Network and the Sci Fi Channel and hired Chao as president of programming and marketing. Chao is credited with acquiring Monk from ABC. It ran on USA from July 2002 through December 2009, becoming the most popular scripted drama series in cable television history. But before that happened, in November of 2001 Chao resigned as President of USA Cable, a position to which he had been promoted just a year and a half earlier.

During this period Chao’s quirkiness again came through in his choice of housing. In January of 2000 he bought an old 13-unit apartment complex a couple blocks from Santa Monica Bay near Montana Boulevard. He converted six units for his family, four to serve as a big guest house for his mother and the remaining three units into additional guest quarters.

By 2006 Chao had absorbed enough media-building strategies from two decades of association with empire-builders Murdoch and Diller to spawn the WonderHowTo concept along with co-founder Mike Goedecke. They essentially sought to do what his former bosses had done — build a media pipeline that serves up the creativity and passion of others, albeit on a more modest scale. WonderHowTo was initially financed with $500,000 out of the founders’ pockets. It later attracted the Cambridge, Massachusetts venture fund General Catalyst for some series A funding.

The richest man in Los Angeles surfed his way to wealth. Not so much the surfing he does with his actress wife and two kids at the beach, but the pipelines he’s ridden in a rapidly changing healthcare industry.

Patrick Soon-Shiong’s estimated $7 billion fortune owes to a gift for skillfully positioning himself to ride trends that swell into huge opportunities for gain while staring down choppy seas that would have shattered lesser riders into flotsam.

The mental toughness Soon-Shiong developed growing up “colored” under South Africa’s apartheid system helped him thrive in a biotech field that has treated him harshly at times. He has faced suicide by the patient whose remission from diabetes gave Soon-Shiong his first big success, a fraud suit by his own brother, accusations of self-dealing by the investment community and the authorities, attacks on his claims for the efficacy of supposed wonder drugs. It all culminated in two multi-billion-dollar paydays.

While winning many admirers for his generosity Soon-Shiong has also incurred the resentment of neighbors by snapping up a block of ordinary homes, tearing them down and combining them into a 3-acre pad for a mega-mansion to share with his actress wife and two children. As if that isn’t obnoxious enough, he has also recently bought a chunk of the L.A. Lakers and uses it to put a full-court press on key business prospects.

And at the age of 58 Soon-Shiong isn’t about to paddle into the sunset with his estimated seven billion dollar fortune. Instead, in early February he has plunked down a chunk of it on a company that could offer him yet another chance to ride the wireless healthcare pipeline to the biggest payday of his career.

Patrick Soon-Shiong was born in 1952 in Port Elizabeth, South Africa to immigrant parents who had fled China during World War II. The family had come from Taishan County, a strategic coastal region about 20 miles southwest of the city of Guangzhou in Guangdong Province. Taishanese have been the most prominent group of overseas Chinese since a large-scale exodus began in the early 1800s triggered by natural disasters and the colonization that followed China’s defeat to Britain in the First Opium War (1839-1842). The Japanese invasion a century later triggered another wave of emigration from Taishan. Among them were the Soon-Shiong family (originally surnamed Wong). Emigration from Taishan was so heavy that by the mid 20th century about 75% of all Chinese Americans traced their origin to that region.

Patrick’s father had been an herbalist in China. In South Africa the elder Soon-Shiong continued to practice herbal medicine though his main source of income was the family’s general store.

“My father was a village doctor, practicing Chinese herbal medicine,” Patrick told an interviewer from Los Angeles Business Journal in October of 2008. “People would come to the house for advice. He’d make up some herbal concoction to give them. I’d watch all that. It was very inspiring and influences what I do today.”

Patrick’s ambitions faced barriers imposed by South Africa’s apartheid system under which Chinese were legally second-class citizens. Only toward the latter part of the 1970s, after South Africa established diplomatic relations with Taiwan, Japan and South Korea, were some Asians accorded “honorary white” status. Even so non-whites had no hope of being admitted to medical school without exceptional qualifications. Patrick graduated from high school at age 16 with good enough grades to win acceptance to the University of Witwatersrand Medical School.

Many Asian standup comics have lines — the kind they seem unwilling to cross. For example, they seem constrained by lines that keep them from being macho and openly sexual. Eliot Chang isn’t. In one of his routines he talks up his penis size. In his own video promo he toys with three buxom women.

Another pleasant surprise: Chang doesn’t seek laughs by ridiculing Asians. In fact, his acts rarely involve ethnicity. When they do, it’s to ridicule people who mock Asians. A topic to which he does seem particularly drawn are the vanities and foibles of young women. His acts have zeroed in on girls who update their facebooks too frequently, the impossibility of snapping one picture for a group of women, the way women refuse to let boyfriends short-circuit arguments.

Eliot Chang is the stud among the current crop of young Asian American standup comics. His facial features are almost too regular for a comedian. He’s a sharp dresser whose clothes show off bulging biceps and sculpted torso. He’s utterly comfortable with his sexuality. In one act he riffs about his fondness for loud, apartment-rousing sex.

The balls-out style carries over to the way Chang works. Unlike most professional comics who hone jokes on paper before firing them at live audiences, Chang takes the stage on inspiration and improvises. He doesn’t write the material down until he’s performed it at least three times to get the kinks out.

It’s working. At the moment Chang is more than holding his own against a small army of comics on Comedy Central’s Standup Showdown 2011. He’s determined to be among the top 10 when the contest ends January 27. So far he’s among the top but he has been pushing everyone to vote for him once a day at http://bit.ly/gBVILr or by texting “CHANG” to 44686. Actually, he’s encouraging fans to DOUBLE their votes by doing both.

Chang’s intense — not to say maniacal — performing style is in sharp contrast to his obsessive concerns about privacy. We got him to disclose that he was born in Queens, New York on September 27, but not the year. He revealed that he graduated with a BS in biology but not the name of his high school or college.

“I don’t want to name exact schools because with the internet these days people can find out so much about you that I want to limit how much information I give out,” he explained. “I hope you understand. I’m just an extremely private person.”

Rick Lee isn’t your run-of-the-mill pornographer. For one thing, it’s not his day job. He prefers to think of himself as a sexual adventurer who happens to record his exploits. Videos of his sexual encounters with about 600-700 women are on his Asian-man.com porn site.

We first learned of Lee back in 2004 through an interview he had done for Masters of the Pillow, a one-hour documentary by James C. Hou featuring a porn film project undertaken by UC Davis Professor Darrell Y. Hamamoto. Goldsea had detailed that project in the article Liberating the Asian Libido, including a brief writeup on Lee.

“My sex life is what I would call ‘diversified’” Lee said on that occasion. “I have friends who are swingers, adult models, and casual dates that I meet online, etc. Many girls on my site are amateur models trying to get into the adult business but there are also swingers, professional porn actresses, girlfriends, dates, etc.

“I don’t choose women to have sex with based on their ethnicity. I choose women who are ok with having sex on camera and they happen to be mostly white. But because they are mostly white, I think it does help the straight Western Asian man image and I feel, like Dr Hamamoto does, that we are emasculated by the media and that we suffer more negative sexual stereotypes than any other race. By being with women of other ethnicities, it brings a bit more balance to the sexual equation and it helps assert the Asian male sexuality.”

As evidenced by the recent Q&A below, Lee’s views on the Asian American male image haven’t changed much, but his life has undergone a dramatic turn.

Goldsea: What motivated you to start Asian-Man.com?

Rick Lee: I noticed there was a lack of straight Asian men in adult entertainment and basically wanted to produce something Asian men (in the west) could relate to. Also, I was tired of all the negative sexual stereotypes Asian men had and I wanted to provide a more balanced view of Asian men. When I first came up with the site, the only Asian men you could find on adult videos were gay men and lady boys.

GS: Is your site a statement, a hobby or a business?

RL: When I first started, my intentions were to just put images of straight Asian men having sex. I was really tired of the stereotypes so in that sense you could say it was more of a statement than anything else. As the site progressed and gained notoriety it became more of a business operation as there were significant costs involved in running the site. However, I always kept it personal and always stayed on the message. My goal to this day remains the same — to help promote the straight Asian image. Money is pretty much last on my list to this day for the site.

GS: You mentioned that porn acting and the site are not your occupation. What is your day job?

RL: Well, first off I never really considered myself a “porn actor”. I shared parts of my sex life with the public but I was never an actor for hire or anything like that. When I started I used to be a business consultant in Silicon Valley but I quit the corporate life in 2002. Right now, I am an investor and have various business interests in different areas.

GS: Is Rick Lee your real name?

RL: This can’t be a serious question :)

GS: Tell us about any experiences that helped motivate you to start Asian-Man.

RL: I’ve always loved women and I’ve always been fortunate in my love life. And when the internet came, I saw it as an opportunity to share my lifestyle with others and show that a regular Asian guy like me can have an extraordinary sex life. I noticed that many Asian American guys had low sexual self esteem and this was my way to help improve that.

GS: Tell us about the first tasks you had to accomplish to get Asian-Man started.

RL: Learning how to build a website. I had everything else I needed to put up the website when I first conceptualized the site, the girls, the cameras, etc. So I pretty much had to learn how to do websites on my own and that was perhaps the most challenging task.

To say that Park Jin-young aka JYP is Korea’s Michael Jackson would be unfair to fans in the rest of the world. Any of Park’s music videos or even ones produced by him for one of his creations — the Wonder Girls among them — instantly establishes him as a first-magnitude talent.

“A superstar is born when you keep hustling after you become a star,” Park told an interviewer. “How are you going to stop yourself from partying every night, drinking, living that crazy life after you become a star? That’s when desperation is needed… Desperation makes terrible singers sing great, desperation makes the worst dancers into the most amazing dancers.”

Park was talking about Rain, the backup dancer he discovered in 2000 and groomed into a big enough pop superstar to fill Madison Square Garden in May of 2006. But he might as well have been talking about himself.

At the age of 38 Park not only retains his mojo as Korea’s most talented singer/songwriter/dancer/choreographer but is emerging as one of the world’s most dynamic music producers. That’s evidenced not only by the success of his namesake JYP Entertainment as a business with about $40 mil. a year in revenues but the caché of his U.S. projects with partners like TV producer Lawrence Bender and the Jonas Brothers and his songwriting and producing of albums for Will Smith, Mase, R. Kelly and Cassie. Park even landed on the cover of Billboard magazine in August of 2007, a first for an Asia-based producer.

Park’s determination to attain superstar status became apparent in July 2007 when — after a six-year hiatus from his own performing career to build JYPE into a global entertainment firm — Park announced his comeback as a singer.

“I will come back as singer Park Jin-young with songs that the fans can enjoy and sympathize with,” he told Chosun Daily soon after the opening of JYPE’s New York City office on 31st Street. By then Park had already written and produced 30 songs to be included in his new album while working full time as JYPE’s globetrotting CEO.

All of Park’s successes spring from his monster talent. He owns the closest thing most will ever see to Michael Jackson’s id-fueled, spring-loaded moves. Park’s singing voice oozes angst and speaks to everyman’s demons. But Park’s true power resides deep inside where his creative juices spring. That creative intensity is reflected in a face that evokes the dark, maniacal and compellingly charismatic mugs of, say, Jack Nicholson, Frankenstein and the green god Loki in The Mask. Park’s demeanor ranges from bored lounge lizard to conscience-racked cannibal. One look at Park’s face tells audiences that this man digs deep beneath conventional pop sentiments to claw at those unspeakable urges that rarely see the light of day.

As a producer Park shows remarkable fluency with imagery. Tears crystalize on his cheek as he’s being caressed on a crowded harem bed to suggest ritual grief at the eternal conflict between love and desire in his “No Love No More” music video (whose release roughly coincided with his March 2009 divorce from his wife of 10 years). In the Wonder Girls’ witty U.S.-debut music video “Nobody” (2009), in a bit of self-parody, Park plays an ego-centric star stuck in a toilet before a big show.

In short, Park is the antidote to the sterile prettiness of most pop artists. It’s doubtful that even Park’s own JYPE Academy could have created a Park Jin-young.

Park Jin-young was born in Seoul, Korea on January 13, 1972. From an early age he showed himself to be a maverick, an artist, an oddball — in keeping with his AB blood type, his fans might opine. His misfit personality got him into so many fistfights that he recalls being covered with bruises during the entire three years of junior high. He also had his own way of studying. As a high school senior he slacked until the last 100 days before his college entrance exam, then slept three hours a night while cramming. It worked well enough to get Park into Yonsei University, about like Korea’s Columbia.

At Yonsei Park recognized that his lifelong love of music and dance was taking precedence over his studies. He decided to be a singer-dancer who attended Yonsei and not a geologist who can sing and dance. For two of his college years Park lived with a composer/producer who helped shape his raw talent into an album released in 1994 under the title Blue City. Its sexy and provocative lyrics scandalized some. The slick dance moves Park worked into his stage performances helped turn the single “Don’t Leave Me” into one of the year’s top hits.

When we started spotting bottles of Sriracha sauce at decidedly non-ethnic restaurants and markets, we knew it was time to meet the mind behind the big green-capped bottle that’s starting to replace ketchup on America’s hottest tables.

Problem is, David Tran, the 65-year-old Vietnamese American founder of Huy Fong Foods of Rosemead, California isn’t eager to have the world dip too deeply into the origin of his sauce. One reason may be that, to some extent, its burgeoning sales is based on a happy misconception that Tran may not be eager to correct.

Most people know Tran’s hot sauce as the Sriracha sauce. That’s the most prominent word on the front of the plastic bottles that hold over a pint of the red puree of chili peppers, vinegar, sugar, garlic and salt. Strictly speaking, Tran is misappropriating the name of a Thai sauce named after the beach town of Si Racha in central Thailand. The real sriracha sauce originated as a much thicker, sweeter and tangier paste for use as a seafood dip at local restaurants. The thinner Huy Fong version is usually squirted into bowls of pho and sometimes onto burgers and other foods.

Tran’s sriracha also isn’t the first commercial chili sauce by that name. That title belongs to a Thai company named Sriracha Panich which was acquired by Thai Theparos Foods and sells the sauce under the Golden Mountain brand. If that company moves into the U.S. market with the “Sriracha” brand, a trademark dispute would center around the origin of Tran’s claim to the name associated with his sauce sultunate.

Such abstract concerns haven’t kept David Tran’s Huy Fong Foods Inc from bursting at the seams. In October of 2010 its operations were so cramped for manufacturing space that it signed a deal to build a $40-million 655,000 square-foot headquarters and factory with the City of Irwindale. That’s the biggest new construction started this year in the entire County, according to the LA Times. The City was so eager to snag a big new employer, it’s financing the $15-mil. purchase price for the lot.

Tran’s success has already inspired rival companies to squeeze into the “sriracha” niche. Even the rooster logo and the big clear plastic bottles with bright plastic squirt caps have come under assault. Asian markets often stock several brands of sriracha sauces bearing animal logos ranging from a Vietnamese phoenix, a Chinese shark, a Thai flying goose and even a Thai “cock”. Consumers often do confuse these products with Huy Fong’s. The difference in taste among these brands isn’t always apparent, though David Tran might hotly dispute that assessment.

Tran was a sauce maker since 1975 back in his native Vietnam, he told the New York Times. He used peppers grown on his older brother’s farm in a town north of Saigon. The sauces he made there were a far cry from the one that has become an Asian American household word. He was selling an oil-based sauce in recycled Gerber baby food jars obtained from U.S. military bases. He sold batches to jobbers who distributed them to stores in the region. It became popular as the ideal condiment for roast dog.

By 1979 Tran had saved enough from his business to buy his family’s passage out of Vietnam. After a period of waiting in Southeast Asia for the UN Refugee Agency to resettle them, the family made its way to the U.S. Tran resumed his sauce-making business in a 2,500 square-foot space in Los Angeles Chinatown in February of 1980.

“I remember seeing Heinz 57 ketchup and thinking, ‘The 1984 Olympics are coming. How about I come up with a Tran 84, something I can sell to everyone?’” Tran recalls.

Tran doesn’t dwell on the thinking behind taking the sriracha name for the sauce he decided to produce. The emerging popularity of Thai restaurants around that time probably had something to do with it. But he does recall buying his peppers at Grand Central Market and delivering his bottles in a Chevy van. It was natural that his first sales successes were in the pho shops that had begun sprouting up in and around Orange County, especially the emerging Little Saigon of Westmister and Garden Grove.

In 1996 Huy Fong Foods expanded into his current Rosemead plant, then bought a nearby warehouse once used by Wham-O for frisbees and hula-hoops. Currently the company has grown to annual sales of around $35 million on about 20 million bottles of hot sauce. But about 80% of Huy Fong’s sales continue to be to Asian American outlets and the company remains a family affair, employing eight family members and a total of 70 seasonal manufacturing workers. Tran’s 33-year-old son William is now the company president.

The popularity Huy Fong’s sriracha sauce has since attained as a way to spice up everything from burgers to sushi took Tran by surprise. During the past two years chefs at restaurants from Appleby’s to the most chi chi Manhattan bistros have begun proclaiming their devotion to sriracha sauce as a secret ingredient of some of their dishes. More importantly from considerations of sheer sales volume is its recent jump from ethnic markets like Ranch 99 to generic outlets like Wal-Mart and major regional supermarket chains.

At this point demand is so strong that the only thing holding back an immediate tripling of production is lack of space. In fact, once the business moves into the new Irwindale building it will begin ramping up manufacturing capacity tenfold by 2016 just to keep up with backlogged demand.

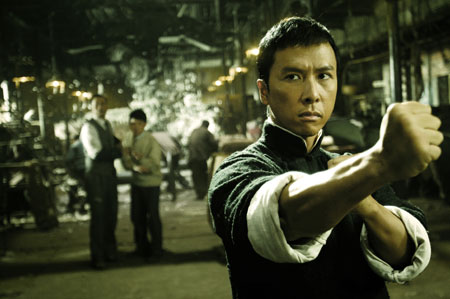

Bruce Lee. Jackie Chan. Jet Li. These are the names that define the martial arts genre. For the next generation of moviegoers another name is moving up into the pantheon: Donnie Yen.

Martial arts stars have always been made in Hong Kong, and Donnie Yen is already considered Hong Kong’s top action star.

“Every one or two decades a new wave of action stars evolves for the generation,” notes Peter Chan, one of Hong Kong’s most successful film producers and directors. “We had Bruce Lee in the 60s and 70s, Jackie Chan and Jet Lee in the 80s and 90s. Now it is Donnie Yen. He has built himself into a bona fide leading man who happens to be an action star.”

Donnie Yen was born in Guangzhou in China’s southeastern Guangdong Province on July 27 1963. His family moved to Hong Kong when he was two, then immigrated to the U.S. when he was eleven. As soon as he could walk he was taught martial arts by his mother Bow Sim Mak, a renowned Tai Chi master and a founder of the International Institute of Chinese martial arts.

While growing up in Boston Donnie picked up martial arts moves from watching Bruce Lee movies. He also studied a wide variety of martial arts styles. His teen rebelliousness, including rumored involvement with a Boston Chinese gang, worried his parents. They sent him to China’s Beijing Shichahai Sports School for two years of moral education and professional martial arts training with its famous Wushu team.

Another force in Yen’s early life was music. His father Zhen Yun Long, an editor of the international Chinese newspaper “Sing Tao Daily” in Boston, plays the violin and the erhu, a Chinese stringed instrument. He influenced Donnie to study classical piano. To this day Yen particularly admires Chopin. His younger sister Chris Yen is also a martial artist and actress. She appeared in film Adventures of Johnny Tao: Rock Around the Dragon (2007).

Yen began his career in Hong Kong’s film industry during the 1990s when kung fu films had fallen into decline. Back then, Yen was 19, finishing his training in Beijing Shichahai Sports School. On his side trip to Hong Kong before he returned to the U.S., he met film director Yuen Woo Ping. Yen’s talents and his physical quality deeply impressed Yuan. Upon his return to the U.S. in 1982 Yen entered a local martial arts competition and won the championship, which solidified Yuan’s impression with Yen. This ultimately led to Yen’s first movie, Miracle Fighters 2, and subsequently “Drunken Tai Chi”, where he played a leading role for his first time, with both movies directed by Yuan.

Yen’s martial arts skills won him many parts as policemen and martial arts masters. In his early career Yen won acclaim for the HK TV version of the movie Fists of Fury in which he played Chen Zhen. It was the same role played by Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan and Jet Lee. Yen’s fans took to calling him Chen Zhen.

Another of Yen’s early successes was Tiger Cage 2 (1992), a cop story with nonstop action. Playing a recalcitrant ex-cop, Yen revealed a delightful comic flair that is utterly missing in his other films. The fight scenes in that film are also considered some of the best of the action genre. Industry professionals were also deeply impressed by Yen’s choreography and fluent display of varied fighting styles.

The apex of Yen’s career to date was reached in 2008 with his starring role in Ip Man, a biopic about the Wing Chun grandmaster who taught Bruce Lee. “Yen perfectly exhibit the Wushu of Wing Chun, and sufficiently shows Yip Man’s master temperament as well as his characteristics,” raved Yip Man’s family. This film won widespread acclaim from critics and audiences while grossing over US$21 million worldwide.

Shen Tong was the chief peace negotiator on behalf of the students who led the democracy movement that ended in the June 4, 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.

Shen Tong was the chief peace negotiator on behalf of the students who led the democracy movement that ended in the June 4, 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.