I just watched with moist palms as Vania King and partner took a seesaw three-setter in whipping gusts for a slot in Sunday’s U.S. Open women’s doubles final. I don’t watch doubles but made a point of watching because Vania is Chinese American. I lived and died by her sparkplug style, coolness under fire, decisive generalship, steadiness with serves and lightning volleys on the big stage of Louis Armstrong Stadium as I had done while watching her and her ethnic Russian Kazakh partner Yaroslava (the converse of Vania, in racial terms) win the Wimbledon Championship in June. Vania is Asian American through and through, and my heart beat with hers during those matches.

The same heart beat inside the publisher of Transpacific and Face.

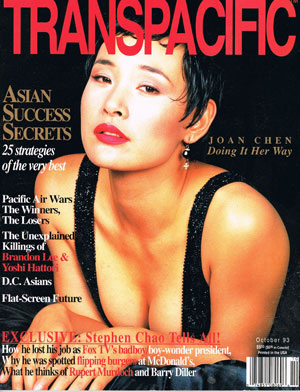

Transpacific and Face helped change the Asian American image in the mainstream media by becoming a hard-copy reference for all who sought accurate information on Asian Americans.

A big challenge was getting advertisers to visualize the real audience. By the mid-1990s nearly half of adult Asian Americans were professionals, entrepreneurs or managers, and over two-thirds were fluently bi-lingual or spoke only English. Asian professionals were rapidly becoming the backbones of IT, medicine, engineering, academia and financial services. People like An Wang, Bill Mow, I.M. Pei, Charles Wang, Steve Kim, Andrea Jung, John Tu and James Chu (among the many successes profiled in great detail in Transpacific and Face) were changing the face and pace of American business. Yet America’s picture of us remained frozen in time as immigrants with limited English skills who worked in sweat shops or, at best, ran green grocers.

To some extent this misconception was perpetuated and exploited by ethnic-language newspapers and advertising agencies who naturally touted the primacy of in-language media and discounted English use among Asian Americans. Only by correcting Madison Avenue’s perception one corporate marketer and advertising executive at a time were Transpacific and Face able to add prestige advertisers like BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Cadillac, Estée Lauder, Tiffany and Lancome, among many others.

Their intelligent articles and widespread distribution made Transpacific and Face a convenient hard-copy representation of Asian America for all who wanted to know who we are, how we live, how we think, and how we see ourselves. The availability of this resource produced a visible change in mainstream awareness and, consequently, in the way Asians are now portrayed in American commercials, TV shows and movies.

Another prejudice that Transpacific and Face helped dispel were those held by U.S.-born Asians about immigrant Asians. Throughout the 70s and 80s the term F.O.B. (fresh-off-the-boat) was used to dismiss immigrants as the uncouth source of comical stereotypes about Asian Americans. In those days the majority of Koreans, Vietnamese and Chinese had been born overseas. Consequently entire nationalities were dismissed as F.O.B.s by U.S.-born Chinese and Japanese Americans. Transpacific and Face showed by many impressive examples that the vast majority of the most successful Asians in U.S. business, technology, medicine and education represented the recent influx of Asia’s brightest and most ambitious. What’s more, young immigrant Asians and the children of recent immigrants were swelling Asian ranks at top universities on both coasts.

The in-depth portrayals of Asian American success stories in Transpacific and, to a lesser extent, Face, showcased the magnitude of immigrant Asians’ contributions to an American society awakening not only to sushi, karaoke and killer video games, but its ultimate destiny as a Pacific nation. Their recognition of the achievements of overseas-born Asians helped these magazines build mutual respect and unity within the booming Asian American population. Today only the most out-of-touch Asian American would dismiss Americans born in Asia as inferiors.

Perhaps most importantly, the existence of quality magazines that chronicled and celebrated Asian American success and lifestyle helped evolve our own self-images away from the cold margins and toward the warm center of American society. With an abundance of role models, complete with blow-by-blow accounts of how they struggled and succeeded as Asians in America, ambitious young Asian Americans were able to pursue their goals with the confidence of those at the forefront of a more dynamic and cosmopolitan America.

Their visibility and their many upscale national advertising which had before been seen in Asian publications in this country made Transpacific and Face appear wildly profitable. About two dozen starry-eyed competitors jumped into the business during the 1990s. Most published a handful of issues before surrendering to the brutal and unforgiving economics of glossy magazine publishing. But their transient efforts helped the Asian American cause by adding new voices to the media mix.

They could have saved themselves much pain and gold had they known the behind-the-scenes sweat keeping the gloss on Transpacific and Face. After emptying his bank accounts publisher Tom Kagy had been forced to sell his three houses, including the Bel Air home he was living in. He then sought out wealthy investors, including actor George Takei, the late Japanese Village Plaza developer David Hyun and several successful lawyer acquaintences.

The million of dollars of capital he ultimately pumped in didn’t even buy Kagy respite from the need to pump in sweat equity. He could be found in his office until late each night meeting publishing deadlines. Each morning he awoke at dawn to put in full days as a litigator to cover the big monthly shortfalls from magazine operations. He personally cornered and spent long hours interviewing many of the tycoons and public figures featured in Transpacific. And despite Shi Kagy’s remarkable ad sales success, Tom often felt pressured to pay sales calls to Madison Ave, W. Wacker Drive and Wilshire Boulevard agencies, not to mention local luxury car dealerships and real estate developers. He was all in, and then some. Kagy later admitted that he probably wouldn’t have jumped into magazine publishing had early success in a non-capital-intensive profession like law not warped his business judgment as a brash 30-year-old.

Kagy wasn’t the only publisher who hung on against heavy odds. Another glossy that nearly matched Transpacific for longevity was a pop-culture review called A Magazine. It was started out of a New York loft by Jeff Yang, a Chinese American recent Harvard grad who had cut his teeth on a student publication and had been inspired by Kagy’s magazines. Yang saw a niche not addressed by Transpacific and Face: teens and college students, the so-called Generation Y. With an editorial mix heavy on anime, Hong Kong flicks, K-pop, Canto-pop, J-pop and other icons of the youth scene, A grew from three issues in 1989 to 10 issues a year by the mid 1990s. Its short pieces and flashy graphics treatment appealed to the anime generation and eventually won a place on newsstands alongside Transpacific and Face.

Riding his bike around midtown Manhattan, Yang struggled to convince advertising agencies that A‘s young audience was worth buying. Advertisers like BMW, Estée Lauder, Cadillac, Mercedes-Benz and Chivas Regal could see the value in established professionals who read Transpacific and Face but had little interest in teens and young adults. Eventually A found acceptance with mass-market brands like Pepsi, KFC, Miller Brewing and Chevy. But the advertising volume was too little, too late. Even with money coaxed from his family, Yang had trouble continuing regular publication. In 1998 Jeff Yang sold A’s name and other assets to Click2Asia.com which evolved into one of several emerging Asian dating sites.

Even with a bigger advertising base Transpacific and Face struggled to become profitable. In a do-or-die push to save tens of thousands each month on typesetting, color-separation, stripping and printing costs, in 1991 Kagy installed an Agfa imagesetter about the size of a Volkswagen bug (and eight times as expensive) in the magazines’ Malibu offices. He packed $12,000 worth of extra DRAM and $6,000 worth of extra hard-drive capacity into two Mac Quadras, linked them to the Agfa and coaxed the temperamental imagesetter to spit out fully composed film for overnighting to the printer for plating. Necessity had forced Kagy to become a digital printing pioneer as well as an Asian American media pioneer. It would be three years before most major publishers would come to rely on similar digital publishing setups. That bit of envelope-pushing shaved about $25,000 an issue in pre-press costs. For Kagy that was the margin of survival.

By 1994 the internet was beginning to emerge as a new medium to which Asian Americans were gravitating at a rate that surpassed the American average. In those days AOL was the internet to most people thanks to the easy-access offered by that ISP’s ubiquitous signup CDs. For Kagy the internet’s big lure was the economy and efficiency it offered in reaching his audience. By bypassing the archaic, byzantine and corrupt magazine distribution system, he hoped to escape the crushing economics of a business in which costs always outpaced revenues by a small but unrelenting margin.

His experience with pre-press had made Kagy a believer in technology’s power to solve business dilemmas. Kagy lost no time hiring a web programmer to come to the office to show us how to use the tools needed to build a website. By early 1995 portions of each issue of Transpacific and Face were reformatted for uploading to a domain that essentially sought to replicate the magazines online.

The site reached many Asian Americans who weren’t in the habit of browsing newsstands or subscribing to magazines. By the end of 1996 the site had more readers than the magazines. It was tempting to forsake print, with its huge costs and inefficiency, for the internet. Unfortunately paid banner advertising was still virtually non-existent. Most of the banners on the early internet were served up by banner-exchange networks that were essentially swapping freebies for freebies.

Yet Kagy was highly motivated to push toward an internet publishing model. Not only was he eager to shed the crushing financial burden of publishing print magazines, he had encountered other surprising and infuriating frustrations from unexpected quarters. Among them were midwestern printers.

For glossy magazines with the kinds of color page counts and medium-length print runs of Transpacific and Face, the short-run sheet-fed presses operating in big cities like Los Angeles were simply not cost-effective. Nor was it possible to use printers in Asia due to the time constraints of incorporating advertising pages that often arrived a week before the magazines had to ship to distributors. The long-run printers located in Minnesota, Wisconsin and rural Illinois were the only economical option for magazines like Transpacific and Face. Unfortunately, the workforce at the big bible-belt printers refused to print images or language they deemed offensive to good Christians. On several occasions they stopped presses on Kagy magazines until he agreed to change an offending phrase or swap out a fashion photo they found risqué.

The world wide web promised liberation from these indignities as well as from the loss-making economics of print distribution with the “creative” accounting often used by distributors. But it wasn’t until mid-1998 that Shi Kagy secured the commitment in principle of a few pioneering advertisers willing to pay decent rates for banner advertising. After a 12-year struggle with print publishing, the time had come to launch Goldsea.com.

In Part 3 I will discuss how the internet and its peculiar economics reshaped Asian American media and consciousness, and the role played in that evolution by Goldsea.com and other sites. Next

Read Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4