Why Are All Top US Chipmakers Run by Asians?

By Romen Basu Borsellino | 22 Mar, 2025

The factors behind the dominance of Asian CEOs at top US chipmakers run from the cultural to educational and social.

It’s a clean sweep.

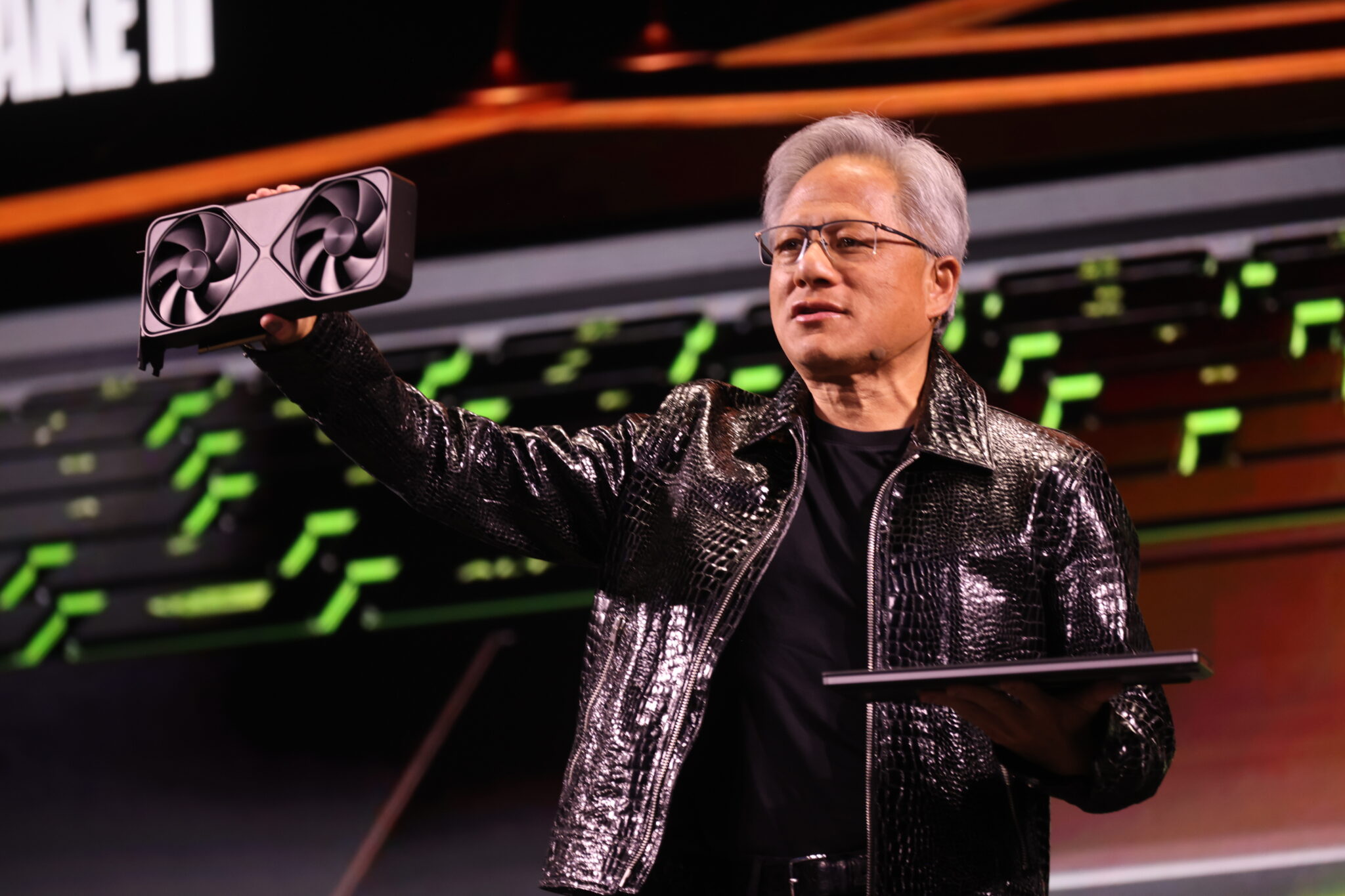

With the appointment of Malaysian born Lip-Bu Tan to run tech giant Intel, Chinese CEOs are now at the helm of the top four semiconductor (or “chips”) manufacturing companies in the United States. Intel’s Tan joins Nvidia’s Taiwanese-born CEO Jensen Huang, and Broadcom’s Malaysian-born Hock Tan to round out “the big three.”

We might even be able to claim 4-for-4 in Chinese dominance depending on how Advanced Micro Devices or “AMD,” run by Taiwanese-born Lisa Su, is doing on any given week (Think of AMD as the “Duke basketball” of chip makers, always liable to make the final four). And while not Chinese, Micron’s Indian CEO Sanjay Nehrota helps Asians claim five of the top ten leadership positions at US semiconductor manufacturing companies.

And we’re not even including Morris Chang, founder and CEO of Taiwan-based TSMC, the world’s top chip foundry, the chip fabrication plant on which Nvidia, AMD and dozens of the world’s other top chipmakers actually rely to produce their chips.

Suffice it to say, there seems to be a pattern.

So what is it about Asians, and specifically the Chinese, that allows them to dominate the highest ranks of this field the same way that Indian kids win spelling bees, Kenyan runners win marathons, and US baseball teams win World Series championships (don’t think too hard about that last one). That’s what we’re going to take a stab at figuring out.

Of course, before we dig into who's making chips, let’s start with a quick primer on what’s even being made:

The product:

A semiconductor, also known as a microchip, looks a lot like its name implies. It’s a tiny fingernail-sized square made of silicon with very small switches on it that effectively power our computers.

To make this as nerdy and pop-culture-y as possible: Remember in Spiderman when Doc Oc dramatically declares “The power of the sun in the palm of my hand” like four different times? These chips aren’t necessarily solar-powered but they definitely fit the cliche. Decades ago, it took equipment the size of a small apartment to carry out the function of these chips.

One particular type of semiconductor chip is the Graphic Processing Unit (GPU) which, while once primarily used for video games, has come to be used largely in the creation of AI tech. Top tech company Nvidia can at least partially attribute their current success to supplying GPUs to companies like OpenAI.

It’s important to note that these companies may be involved in any step of the semiconductor process. Nvidia, for example, outsources the manufacturing of the hardware it designs, whereas Intel is responsible for actually physically making the chips.

Beyond simply knowing what semiconductors are, it’s important to understand just how specialized the process of creating them is.

Specialization:

According to Intel, the factory that manufactures these chips also known as a “foundry” or “fab” costs about $10 billion to make along with a construction process that takes 3-5 years and 6,000 construction workers. Other companies have estimated higher cost and building times, and even the countries that aren’t creating the hardware themselves will need to account for what the factories require to bring their ideas to life.

Even once the factory and its machines are fully functional, producing the chips themselves is a months-long process composed of at least six major steps whose names alone sound complicated: deposition, photoresist, lithography, etch, ionization and packaging. This can take up to 15 weeks. It’s a far cry from, say, firing something off on a 3D printer in minutes.

Any company tasked with building a product that complex requires a leader who understands the ins and outs of that product and the process. This differs from the more traditional role of a CEO. Holding an MBA is simply not good enough. We’ve all heard of a successful businessman stepping into a company’s top leadership spot even if he or she has no direct experience in the field. Take Mitt Romney, for example, who in 1999 left his job as CEO of hedge fund Bain Capital to serve as CEO of the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympic Games Organizing Committee, despite arguably little experience in the field.

A generic businessman with no detailed knowledge of semiconductor creation, known as “the most complex industrial system in human history,” would likely run one of these companies into the ground.

So what the heck does that have to do with Asians?

Patience:

Well, for starters, Asians are known for their patience, which this industry demands more than most. Building just one semiconductor factory might require a decade of planning.

Here’s what I mean when I say patience: Asian-Americans are known to put between 35 and 50% of their paycheck into savings. That’s looking ahead. Asians also tend to invest six or eight years for an advanced or professional degree at about two-and-a-half times the general US population.

Contrast that with an American culture known for convenience. “Fast food,” which the US is known for, is an apt metaphor. And we’re the number one consumer of it, followed by the UK, France, Sweden, and Austria. Only once the list gets to numbers 7 and 9, with South Korea and China, respectively, do Asian countries make an appearance. Maybe it’s representative of a more slow and deliberate psyche.

This sector has never been about finding a quick fix. Nvidia has been around since the early 90s. Intel has existed since the 1960s. These companies are not disruptors like Uber and AirBnB, which didn’t exist 20 years ago. Lip Bu-Tan, for example, has been working in the semiconductor industry since the 1980s. Hock Tan, who built Broadcom through a series of mergers beginning in the late 90s, has a BS from MIT as well as an MBA from Harvard.

Not to mention that every new generation of chips will require repeating large parts of this process. The work will always require planning for the next step.

STEM:

Here’s an obvious fact: Asian culture has strongly embraced the fields of Science, Technology, Education, and Math (STEM). China in particular is running circles around the US when it comes to studying STEM, with one projection showing that universities in China are producing nearly twice as many STEM PhDs as US schools. If you don’t include foreign-born students in the US-count, China is outpacing us threefold. In Silicon Valley, the tech hub of the United States, a gobsmacking 70% of tech workers are Indian or Chinese.

Innovation:

A valid question might naturally be why Asian-born CEOs are thriving in the US rather than their home countries (It’s important to note that this trend is shifting: Since 2012, more than 80% of Chinese students who studied overseas have returned to China).

One big reason why so many qualified Asian CEOs are choosing to lead US companies may be culture. A theory outlined by Business Korea explains that “China's semiconductor industry, developed with government policy support, lacks in attracting high-level talent and innovation,” whereas “the U.S. has achieved technological advancement with a focus on practical innovation and a culture of tolerating failure." This gives the US a leg up on attracting the best of the best.

Connections:

This industry may also be something of a case study in the effects of diversity in the workplace: once some Asians succeeded in running these companies, it was naturally helpful to others. As Reuters described the new Intel CEO, “Tan rubs shoulders with the likes of Lisa Su from AMD and Nvidia's Jensen Huang, two AI chip leaders who, according to Reuters reports, had been pitched to invest in Intel.” Not only that, but Lisa Su and Jensen Huang are actually cousins.

Am I describing nepotism or cronyism? Not necessarily, in that these CEOs are clearly qualified. Not to mention that having these connections is helpful to the job itself given the need to do business with like-minded individuals. Reuters goes on to quote analyst Jack Gold, who believes that Tan "can leverage his experience and especially his industry connections, while also pursuing excellence within Intel.” It is likely that even just a few Asians attaining top spots at these companies allowed for more to follow suit.

Conclusions:

It’s anyone’s guess who will win the semiconductor race between the US and China, particularly given the role of countries like Taiwan and South Korea who have their own world-class chip production capabilities (Taiwan has just announced plans for a $100 billion investment in chip manufacturing plants in the US). But looking at the leaders of the top US semiconductor companies makes it clear that Chinese influence looms large regardless. And while the above overview provides several potential theories as to why this might be the cause, proving them may be a long and complicated process which has to account for numerous moving parts…just like semiconductor manufacturing.

Looking at the leaders of the top US semiconductor companies makes it clear that Chinese influence looms large

Asian American Success Stories

- The 130 Most Inspiring Asian Americans of All Time

- 12 Most Brilliant Asian Americans

- Greatest Asian American War Heroes

- Asian American Digital Pioneers

- New Asian American Imagemakers

- Asian American Innovators

- The 20 Most Inspiring Asian Sports Stars

- 5 Most Daring Asian Americans

- Surprising Superstars

- TV’s Hottest Asians

- 100 Greatest Asian American Entrepreneurs

- Asian American Wonder Women

- Greatest Asian American Rags-to-Riches Stories

- Notable Asian American Professionals