Google Earth Causes Uproar with Maps of Old Japan

By wchung | 07 Sep, 2025

When Google Earth added historical maps of Japan to its online collection last year, the search giant didn’t expect a backlash. The finely detailed woodblock prints have been around for centuries, they were already posted on another Web site, and a historical map of Tokyo put up in 2006 hadn’t caused any problems.

But Google failed to judge how its offering would be received, as it has often done in Japan. The company is now facing inquiries from the Justice Ministry and angry accusations of prejudice because its maps detailed the locations of former low-caste communities.

The maps date back to the country’s feudal era, when shoguns ruled and a strict caste system was in place. At the bottom of the hierarchy were a class called the “burakumin,” ethnically identical to other Japanese but forced to live in isolation because they did jobs associated with death, such as working with leather, butchering animals and digging graves.

Castes have long since been abolished, and the old buraku villages have largely faded away or been swallowed by Japan’s sprawling metropolises. Today, rights groups say the descendants of burakumin make up about 3 million of the country’s 127 million people.

But they still face prejudice, based almost entirely on where they live or their ancestors lived. Moving is little help, because employers or parents of potential spouses can hire agencies to check for buraku ancestry through Japan’s elaborate family records, which can span back over a hundred years.

An employee at a large, well-known Japanese company, who works in personnel and has direct knowledge of its hiring practices, said the company actively screens out burakumin job seekers.

“If we suspect that an applicant is a burakumin, we always do a background check to find out,” she said. She agreed to discuss the practice only on condition that neither she nor her company be identified.

Lists of “dirty” addresses circulate on Internet bulletin boards. Some surveys have shown that such neighborhoods have lower property values than surrounding areas, and residents have been the target of racial taunts and graffiti. But the modern locations of the old villages are largely unknown to the general public, and many burakumin prefer it that way.

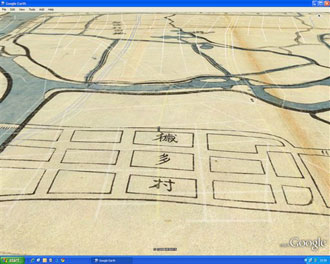

Google Earth’s maps pinpointed several such areas. One village in Tokyo was clearly labeled “eta,” a now strongly derogatory word for burakumin that literally means “filthy mass.” A single click showed the streets and buildings that are currently in the same area.

Google posted the maps as one of many “layers” available via its mapping software, each of which can be easily matched up with modern satellite imagery. The company provided no explanation or historical context, as is common practice in Japan. Its basic stance is that its actions are acceptable because they are legal, one that has angered burakumin leaders.

“If there is an incident because of these maps, and Google is just going to say ‘it’s not our fault’ or ‘it’s down to the user,’ then we have no choice but to conclude that Google’s system itself is a form of prejudice,” said Toru Matsuoka, a member of Japan’s upper house of parliament.

Asked about its stance on the issue, Google responded with a formal statement that “we deeply care about human rights and have no intention to violate them.”

Google spokesman Yoshito Funabashi points out that the company doesn’t own the maps in question, it simply provides them to users. Critics argue they come packaged in its software, and the distinction is not immediately clear.

Printing such maps is legal in Japan. But it is an area where publishers and museums tread carefully, as the burakumin leadership is highly organized and has offices throughout the country. Public showings or publications are nearly always accompanied by a historical explanation, a step Google failed to take.

Matsuoka, whose Osaka office borders one of the areas shown, also serves as secretary general of the Buraku Liberation League, Japan’s largest such group. After discovering the maps last month, he raised the issue to Justice Minister Eisuke Mori at a public legal affairs meeting on March 17.

Two weeks later, after the public comments and at least one reporter contacted Google, the old Japanese maps were suddenly changed, wiped clean of any references to the buraku villages. There was no note made of the changes, and they were seen by some as an attempt to quietly dodge the issue.

“This is like saying those people didn’t exist. There are people for whom this is their hometown, who are still living there now,” said Takashi Uchino from the Buraku Liberation League headquarters in Tokyo.

The Justice Ministry is now “gathering information” on the matter, but has yet to reach any kind of conclusion, according to ministry official Hideyuki Yamaguchi.

The League also sent a letter to Google, a copy of which was provided to The Associated Press. It wants a meeting to discuss its knowledge of the buraku issue and position on the use of its services for discrimination. It says Google should “be aware of and responsible for providing a service that can easily be used as a tool for discrimination.”

Google has misjudged public sentiment before. After cool responses to privacy issues raised about its Street View feature, which shows ground-level pictures of Tokyo neighborhoods taken without warning or permission, the company has faced strong public criticism and government hearings. It has also had to negotiate with Japanese companies angry over their copyrighted materials uploaded to its YouTube property.

An Internet legal expert said Google is quick to take advantage of its new technologies to expand its advertising network, but society often pays the price.

“This is a classic example of Google outsourcing the risk and appropriating the benefit of their investment,” said David Vaile, executive director of the Cyberspace Law and Policy Center at the University of New South Wales in Australia.

The maps in question are part of a larger collection of Japanese maps owned by the University of California at Berkeley. Their digital versions are overseen by David Rumsey, a collector in the U.S. who has more than 100,000 historical maps of his own. He hosts more than 1,000 historical Japanese maps as part of a massive, English-language online archive he runs, and says he has never had a complaint.

It was Rumsey who worked with Google to post the maps in its software, and who was responsible for removing the references to the buraku villages. He said he preferred to leave them untouched as historical documents, but decided to change them after the search company told him of the complaints from Tokyo.

“We tend to think of maps as factual, like a satellite picture, but maps are never neutral, they always have a certain point of view,” he said.

Rumsey said he’d be willing to restore the maps to their original state in Google Earth. Matsuoka, the lawmaker, said he is open to a discussion of the issue.

A neighborhood in central Tokyo, a few blocks from the touristy Asakusa area and the city’s oldest temple, was labeled as an old “eta” village in the maps. It is indistinguishable from countless other Tokyo communities, except for a large number of leather businesses offering handmade bags, shoes and furniture.

When shown printouts of the maps from Google Earth, several older residents declined to comment. Younger people were more open on the subject.

Wakana Kondo, 27, recently started working in the neighborhood, at a new business that sells leather for sofas. She was surprised when she learned the history of the area, but said it didn’t bother her.

“I learned about the burakumin in school, but it was always something abstract,” she said. “That’s a really interesting bit of history, thank you.”

5/2/2009 10:06 AM JAY ALABASTER Associated Press Writer TOKYO

In this computer screen image taken from the Google Earth software, a feudal map of a village in central Japan from hundreds of years ago, superimposed on a modern street map, is shown. The village is clearly labeled "eta," an old word for Japan's outclass of untouchables known as "burakumin." The word literally means "filthy mass" and is now considered to be a racial slur. The burakumin still face prejudice based on where they live or their ancestors lived, and fear that Google's software can be used to easily pinpoint the old villages and match them up with modern neighborhoods. (AP Photo/Google Earth)

Asian American Success Stories

- The 130 Most Inspiring Asian Americans of All Time

- 12 Most Brilliant Asian Americans

- Greatest Asian American War Heroes

- Asian American Digital Pioneers

- New Asian American Imagemakers

- Asian American Innovators

- The 20 Most Inspiring Asian Sports Stars

- 5 Most Daring Asian Americans

- Surprising Superstars

- TV’s Hottest Asians

- 100 Greatest Asian American Entrepreneurs

- Asian American Wonder Women

- Greatest Asian American Rags-to-Riches Stories

- Notable Asian American Professionals